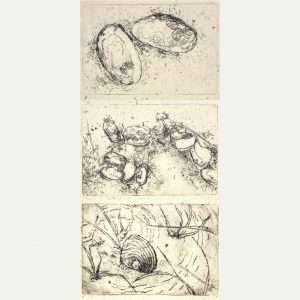

We live in a world where images can be mass reproduced without end. We can trace this history back to the printing press through to the industrial revolution. In response to the growing mass production of printed images, visual artists in the late 19th century revived the creation of the handmade drypoint.

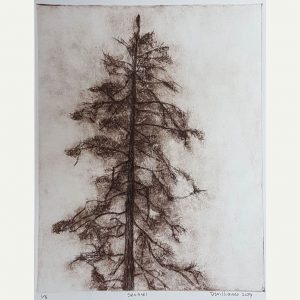

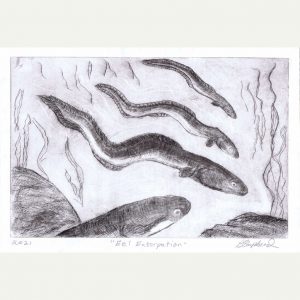

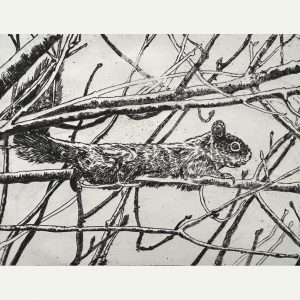

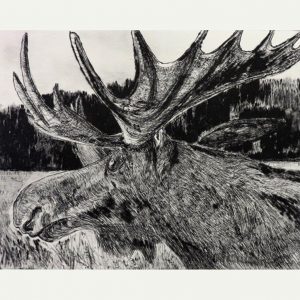

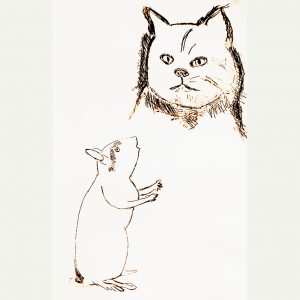

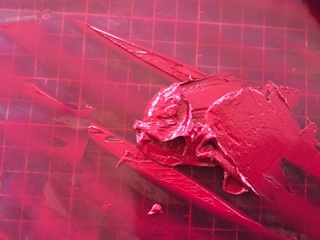

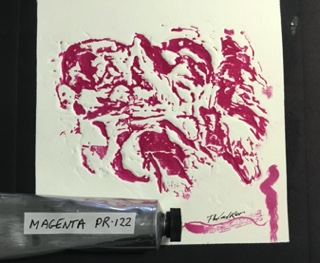

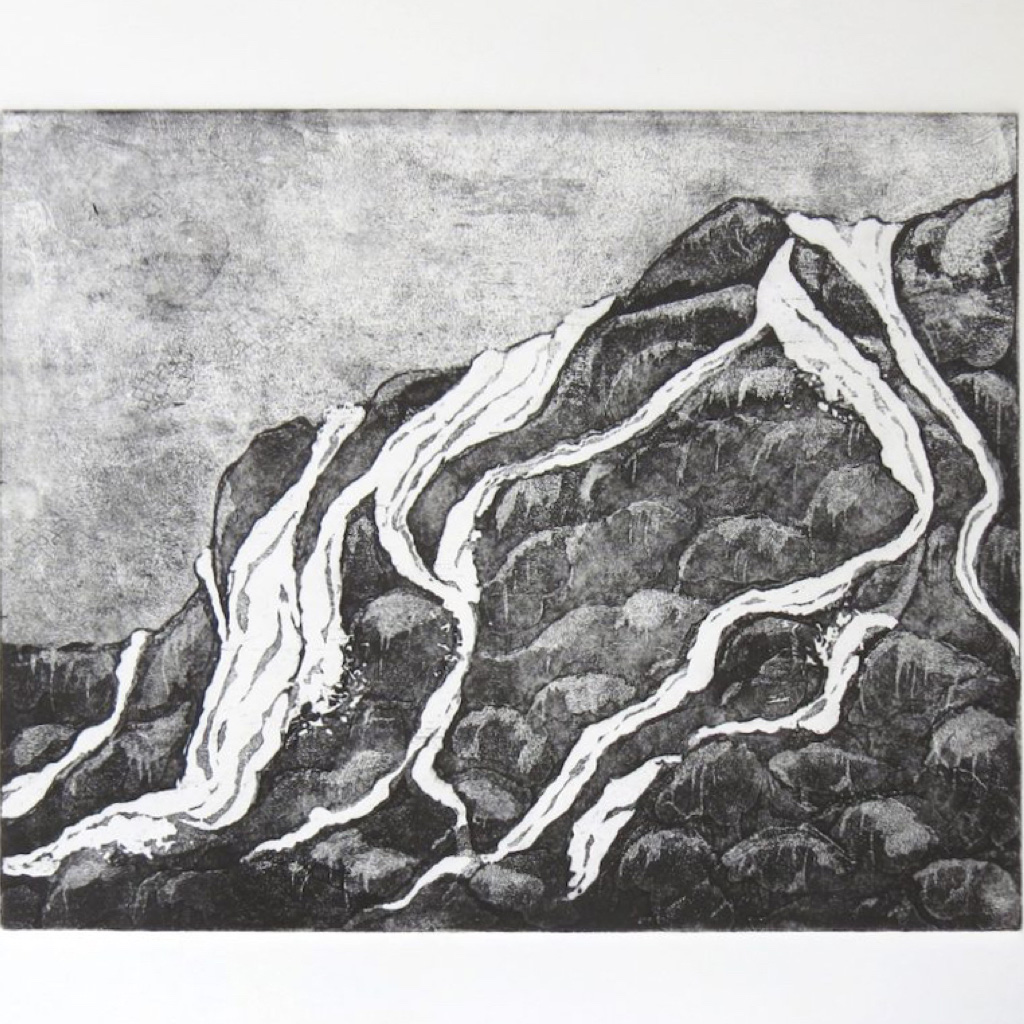

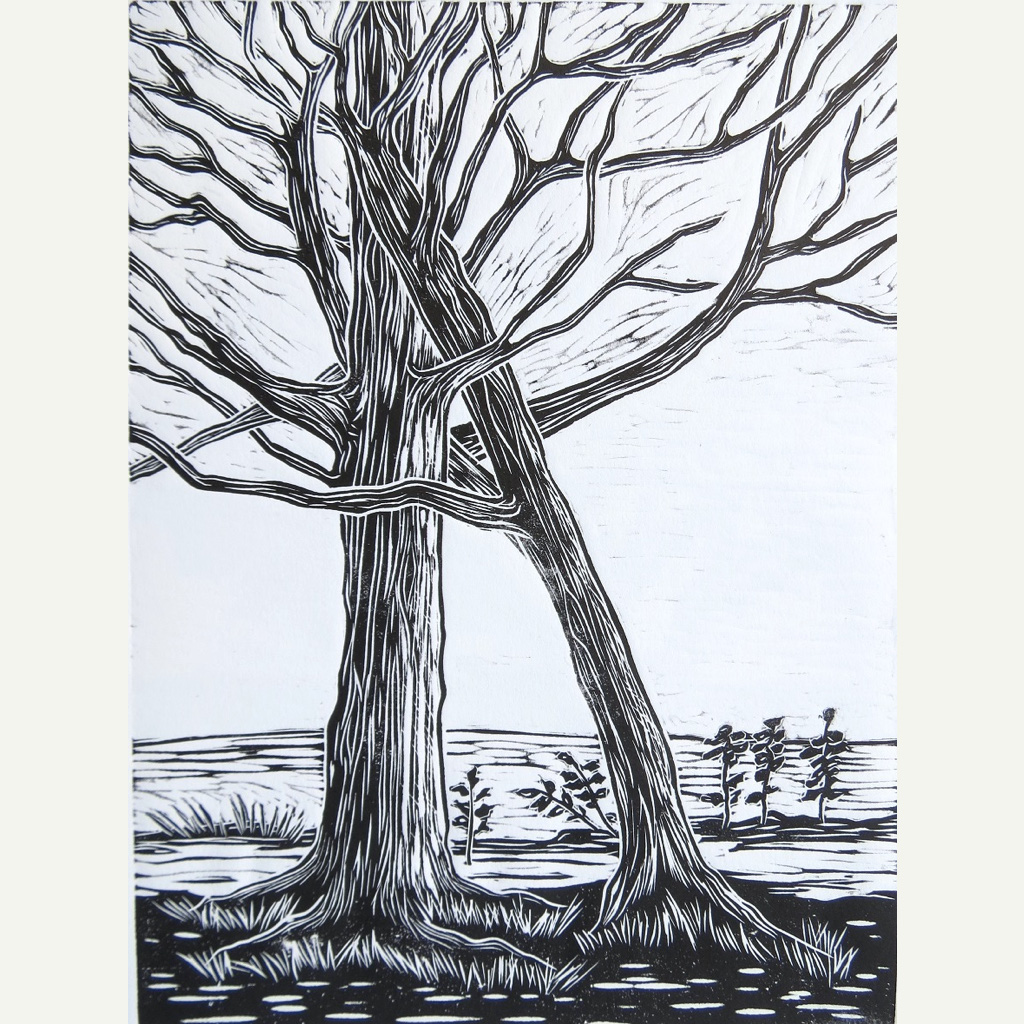

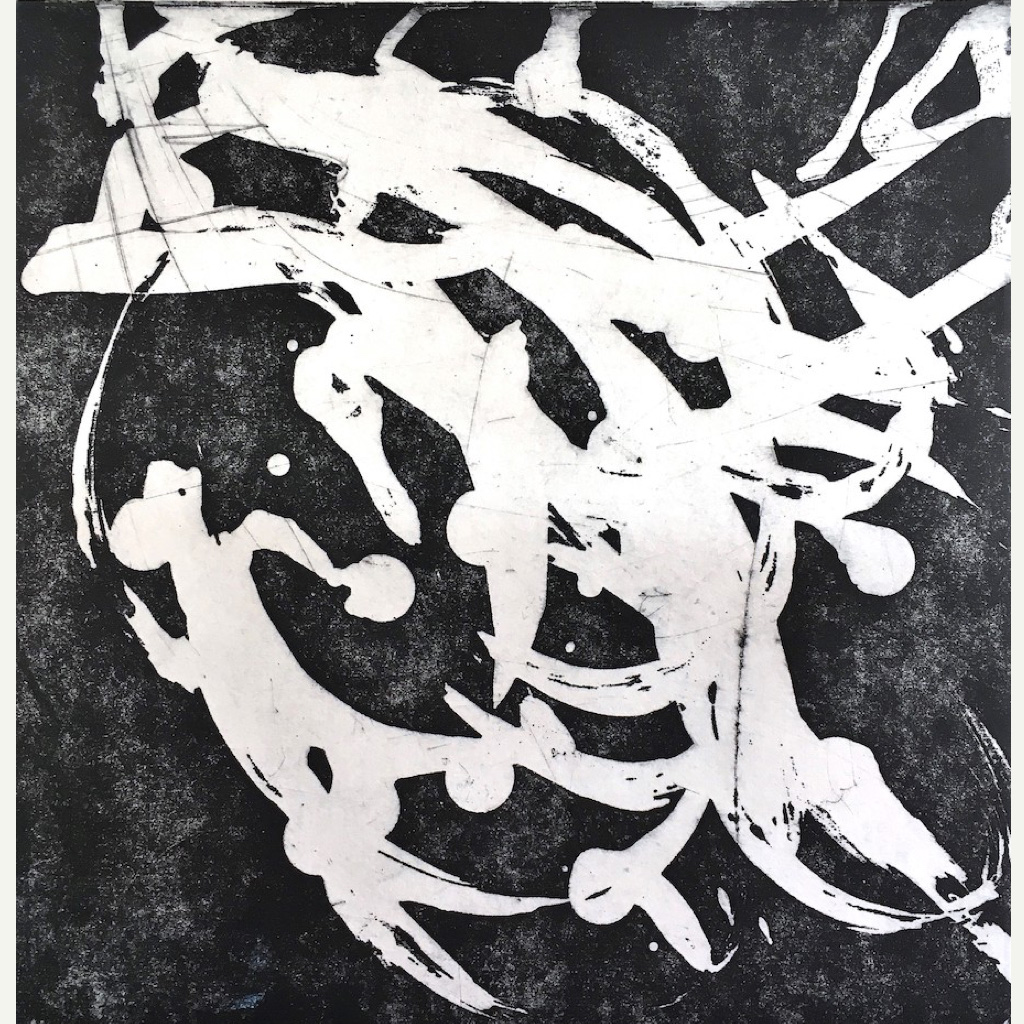

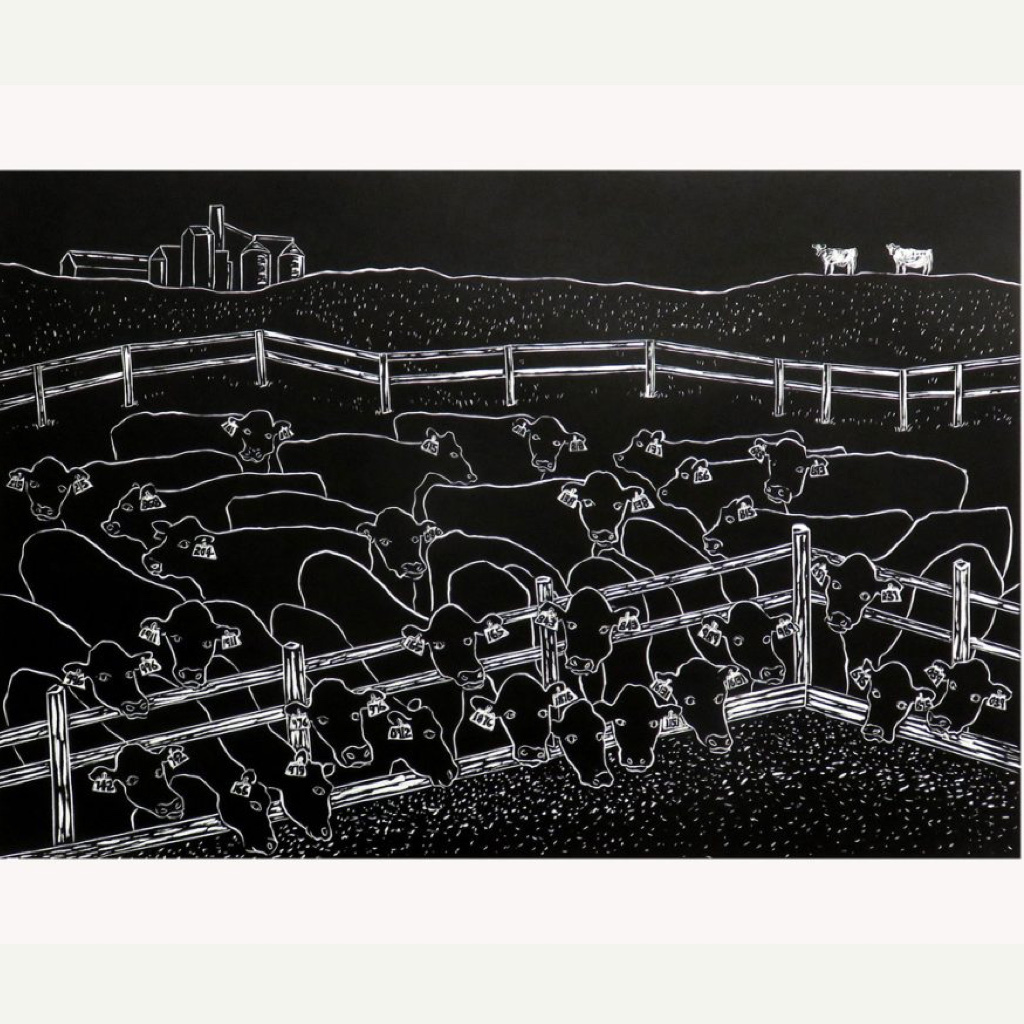

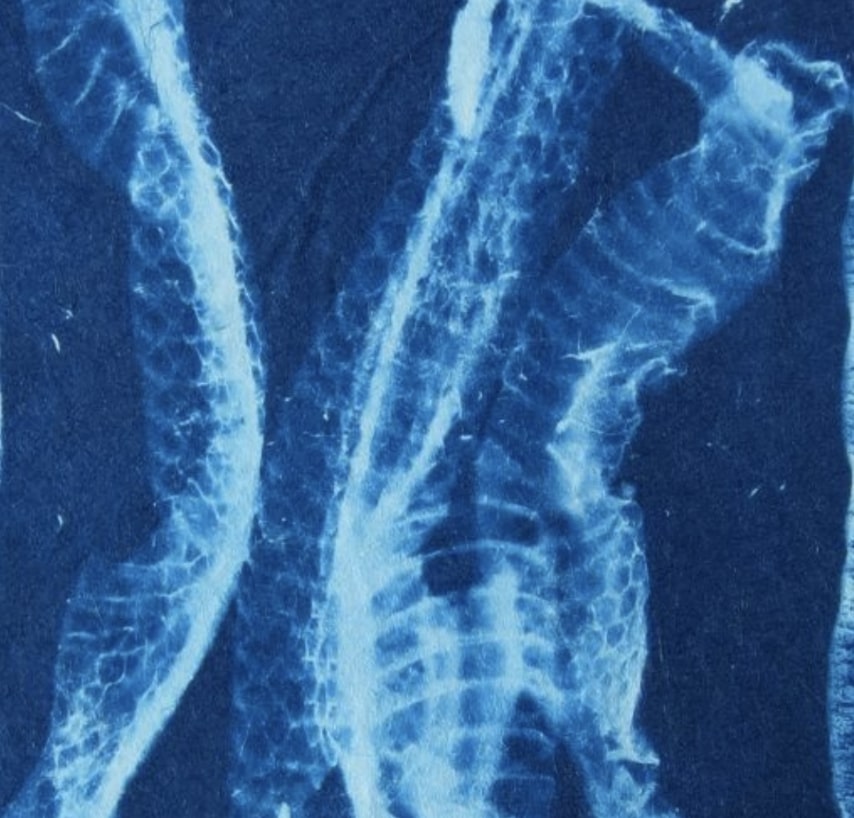

Artists used a stylus to scratch lines directly into a soft metal plate, typically copper. A delicate burr would be raised from the plate. Both the incised line and the burr will hold ink when the plate is wiped. It is this highly coveted burr that creates the velvety soft lines and plate tone that is sought by visual artists using drypoint.

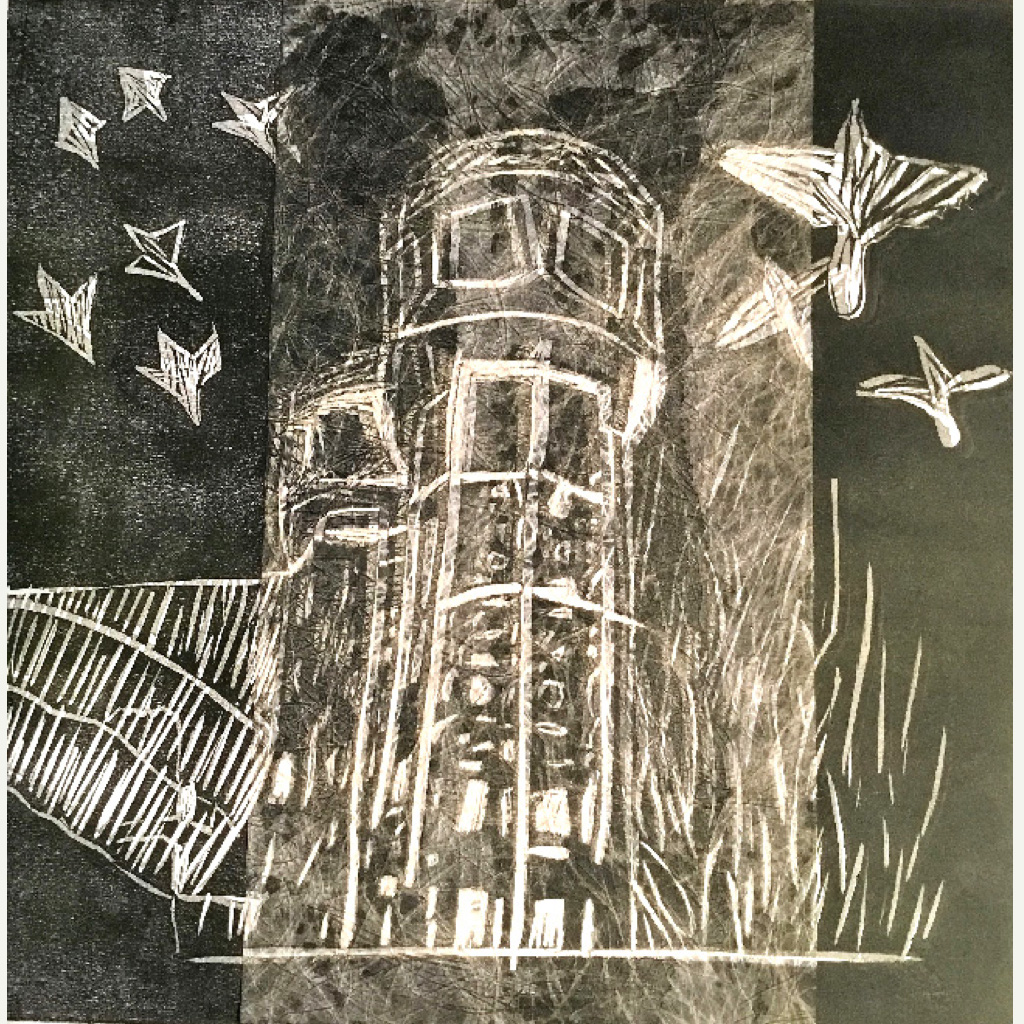

Today, the traditional drypoint technique is still popular with artists. In the last few years, there has been an explosion in experimentation with different surfaces and tools. Dentistry tools, nails and power drills can be used to create lines and textures on various types of flat matrices, such as PVC, plexiglass, PETG packaging plastic and even flattened Tetra packs and plywood. As a result of such experimentation, drypoint and printmaking in general are now more accessible to new and established visual artists.

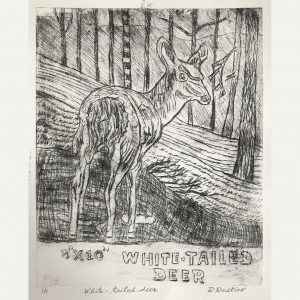

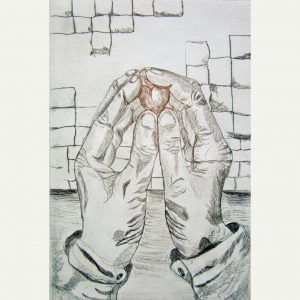

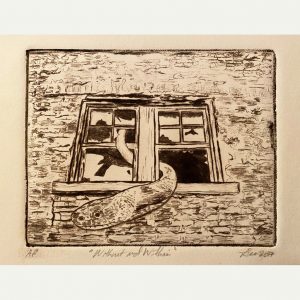

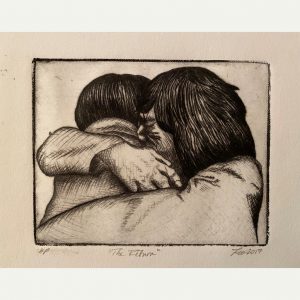

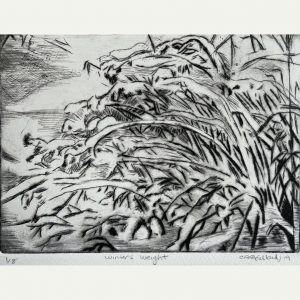

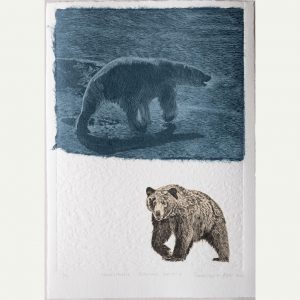

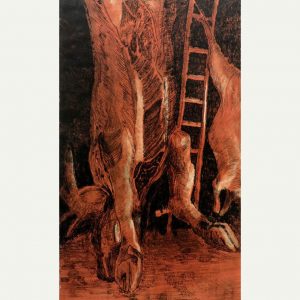

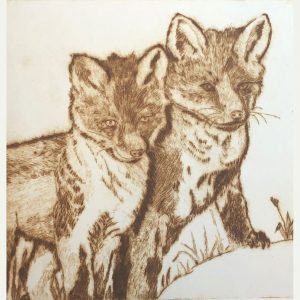

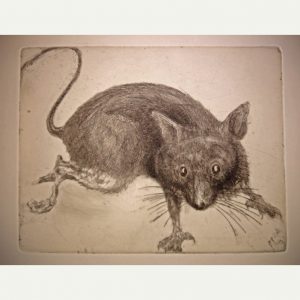

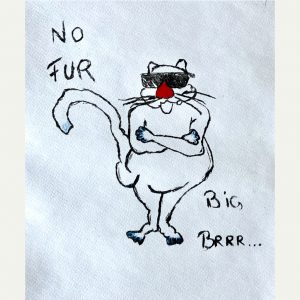

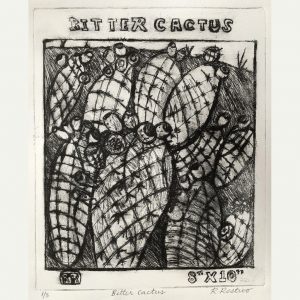

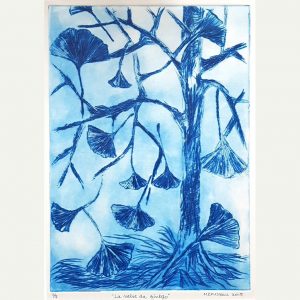

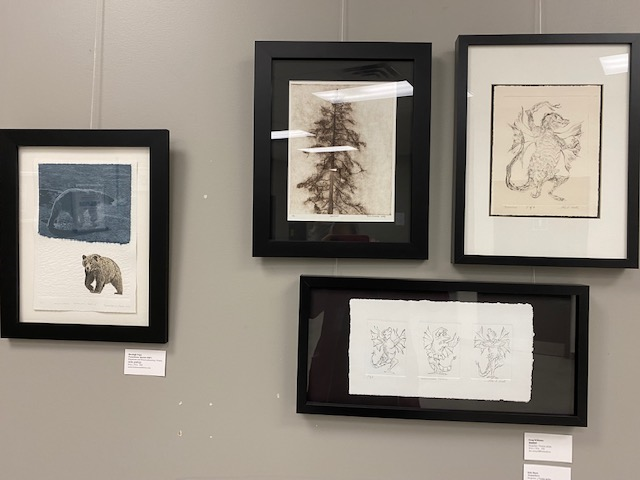

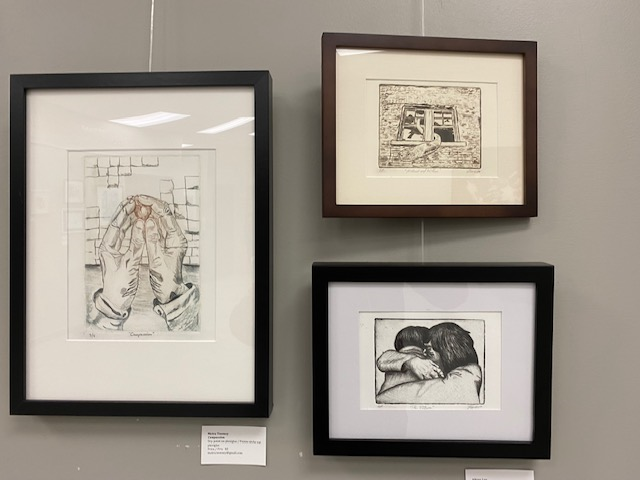

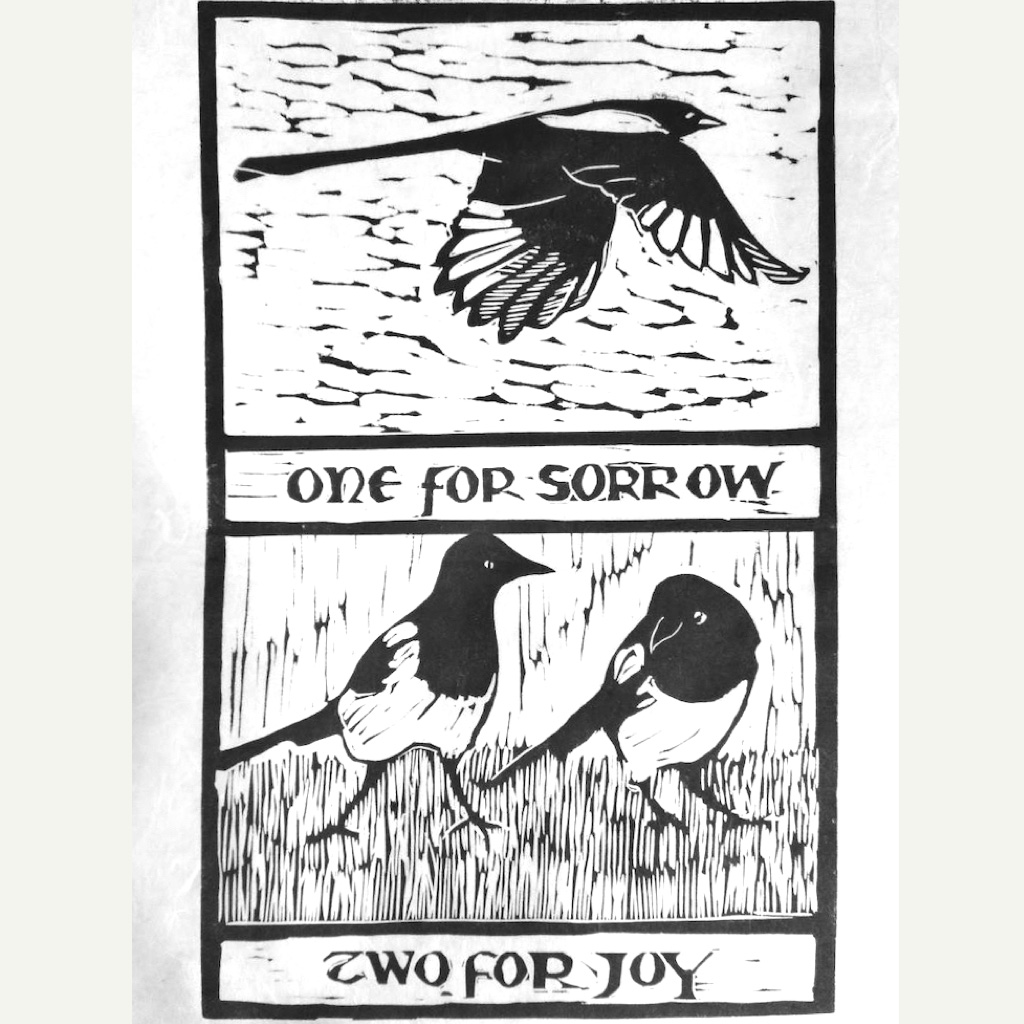

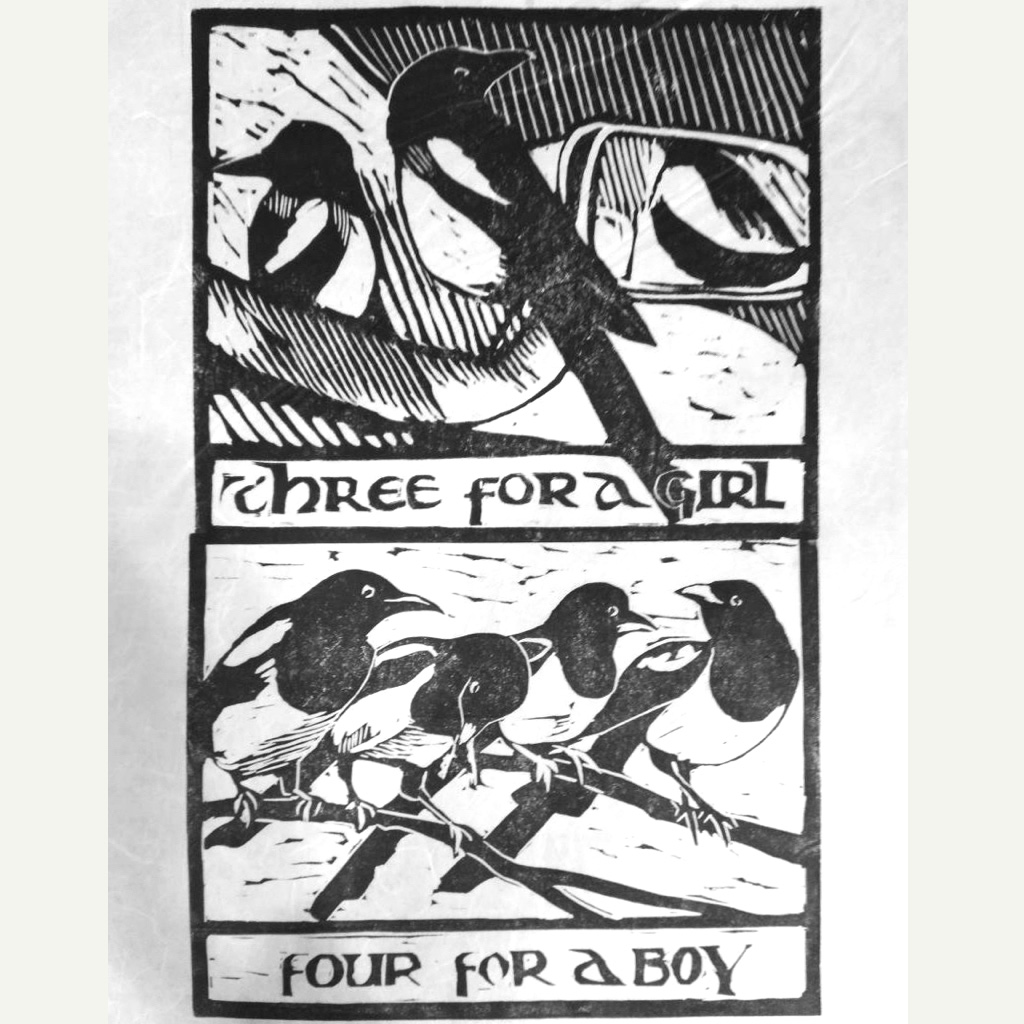

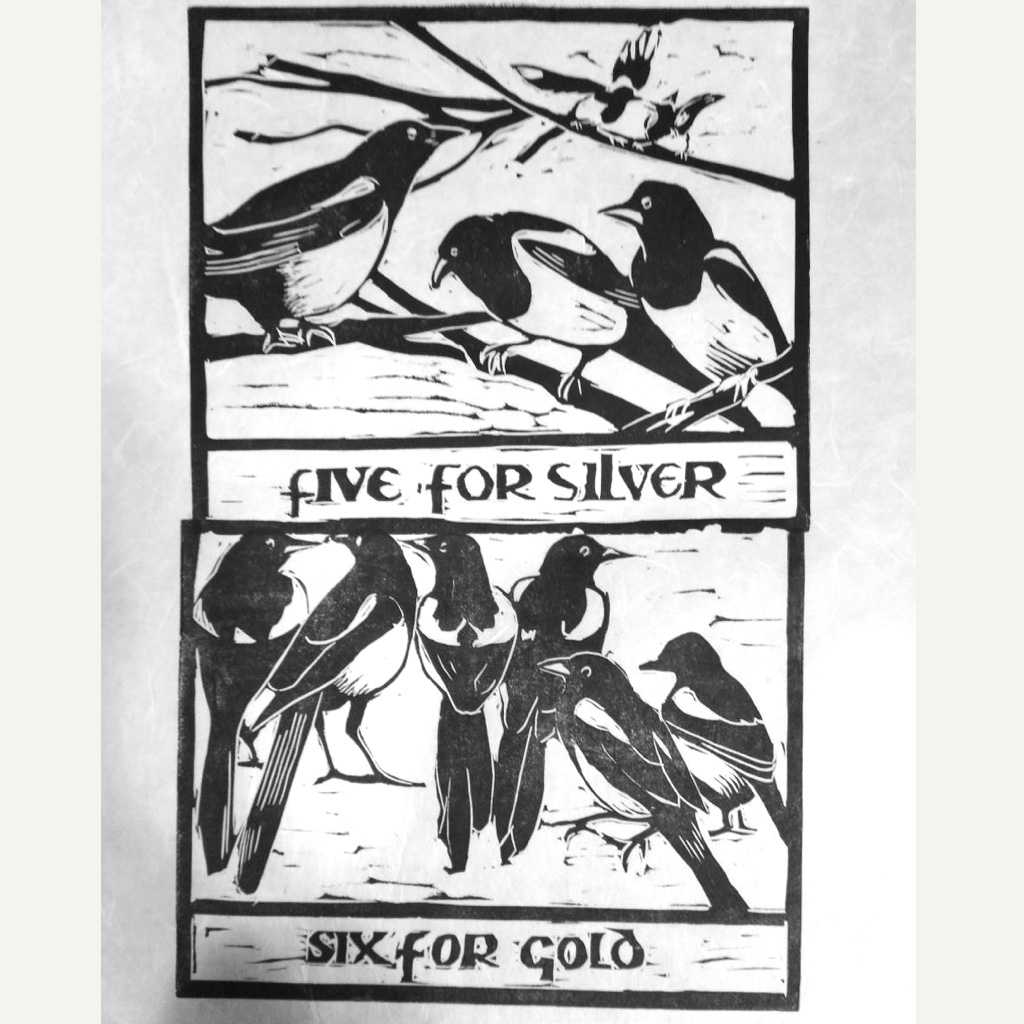

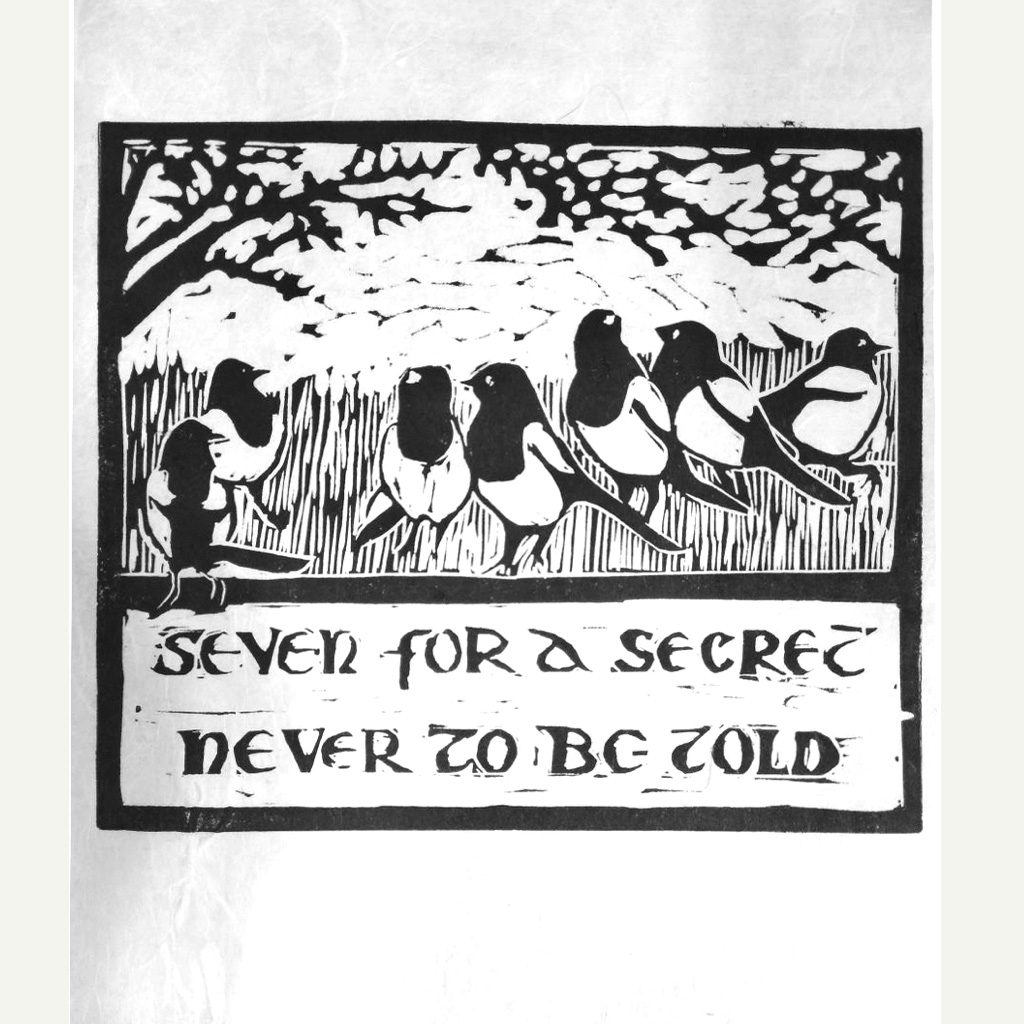

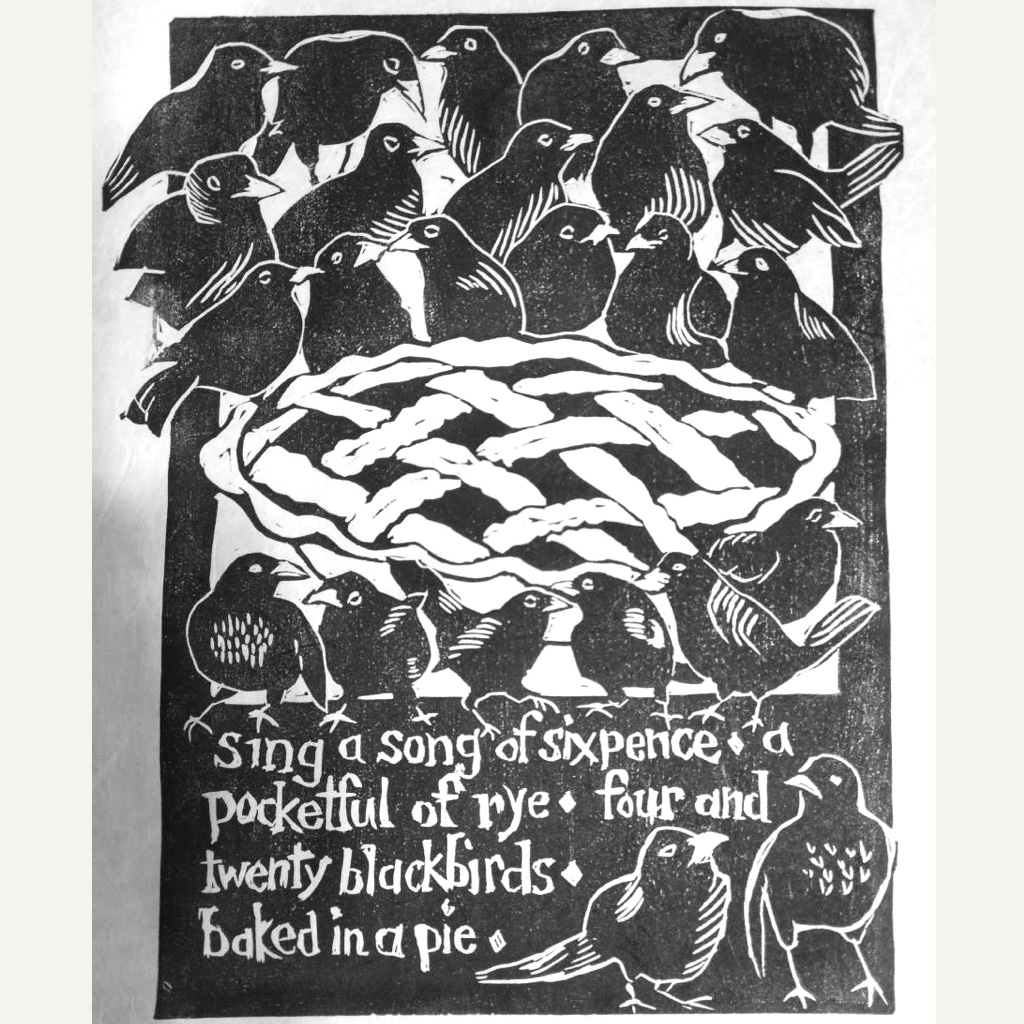

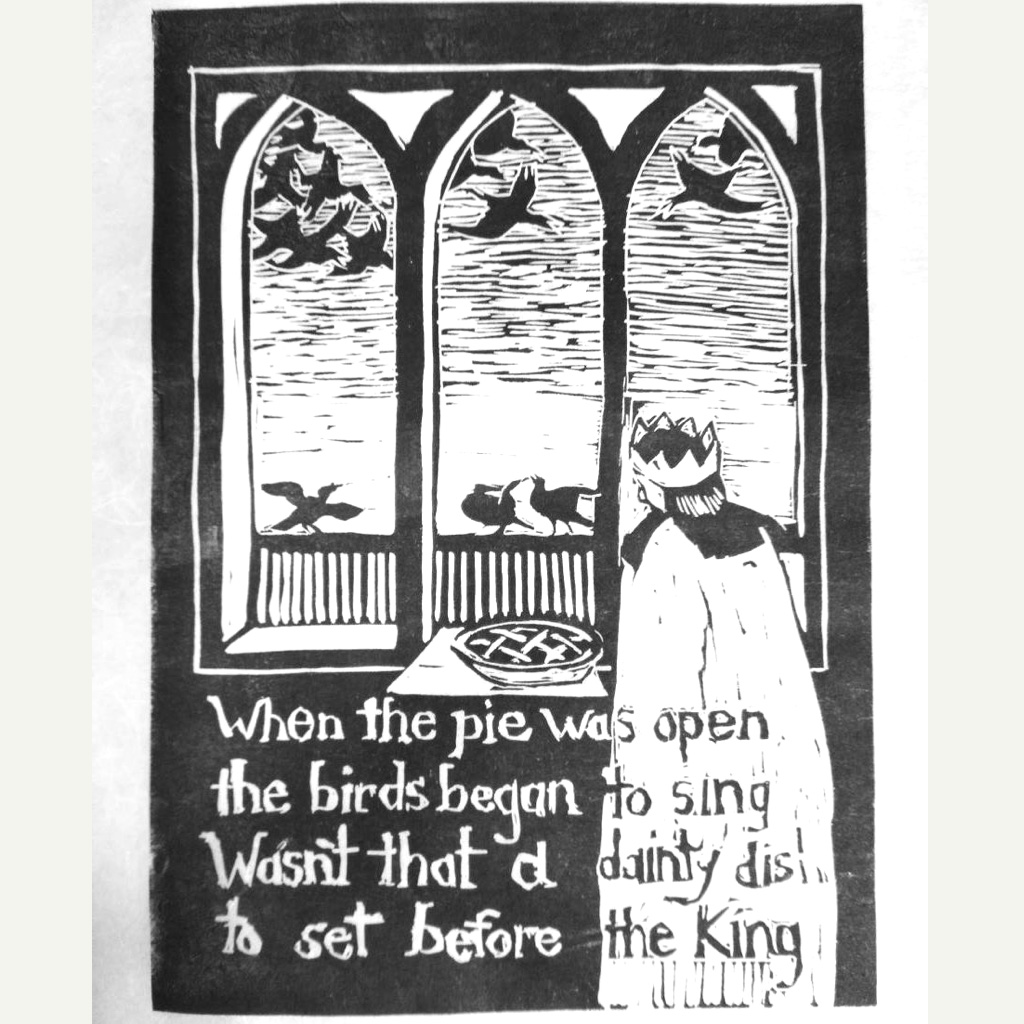

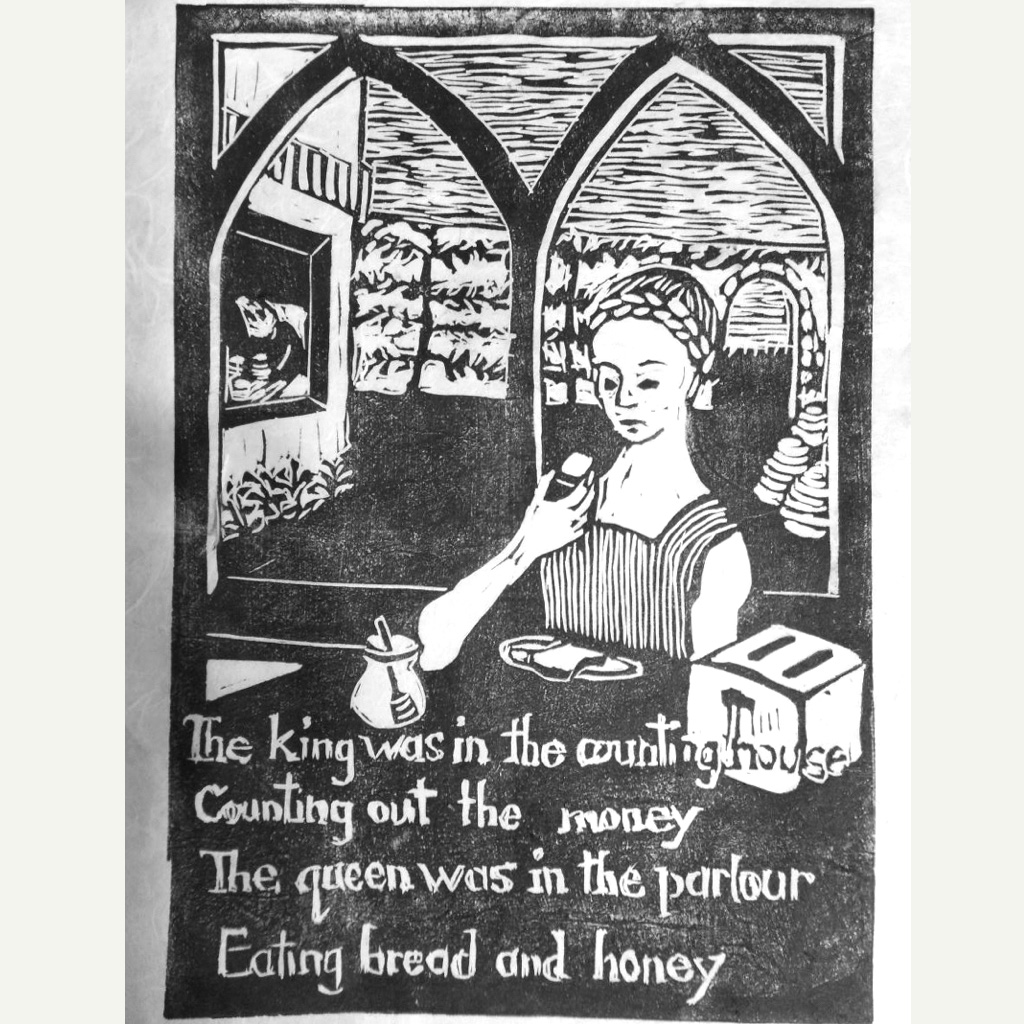

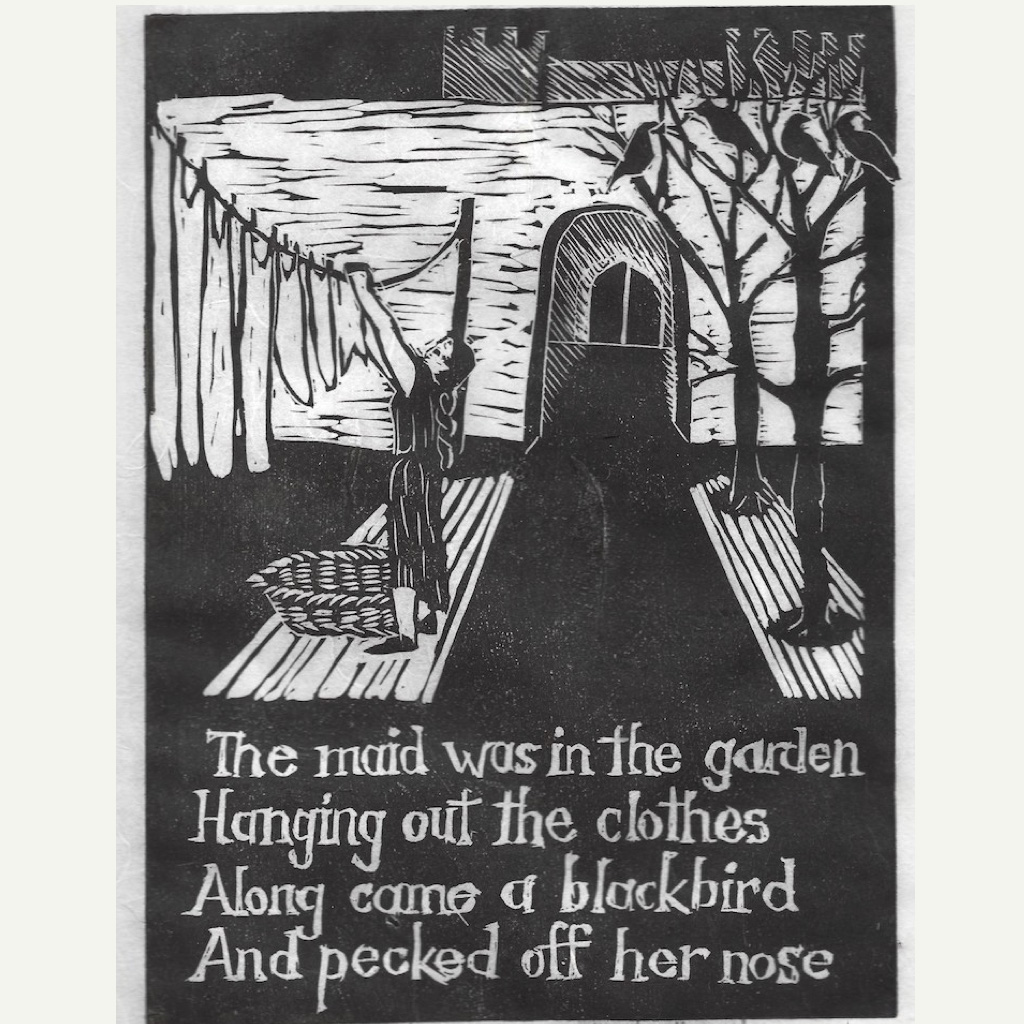

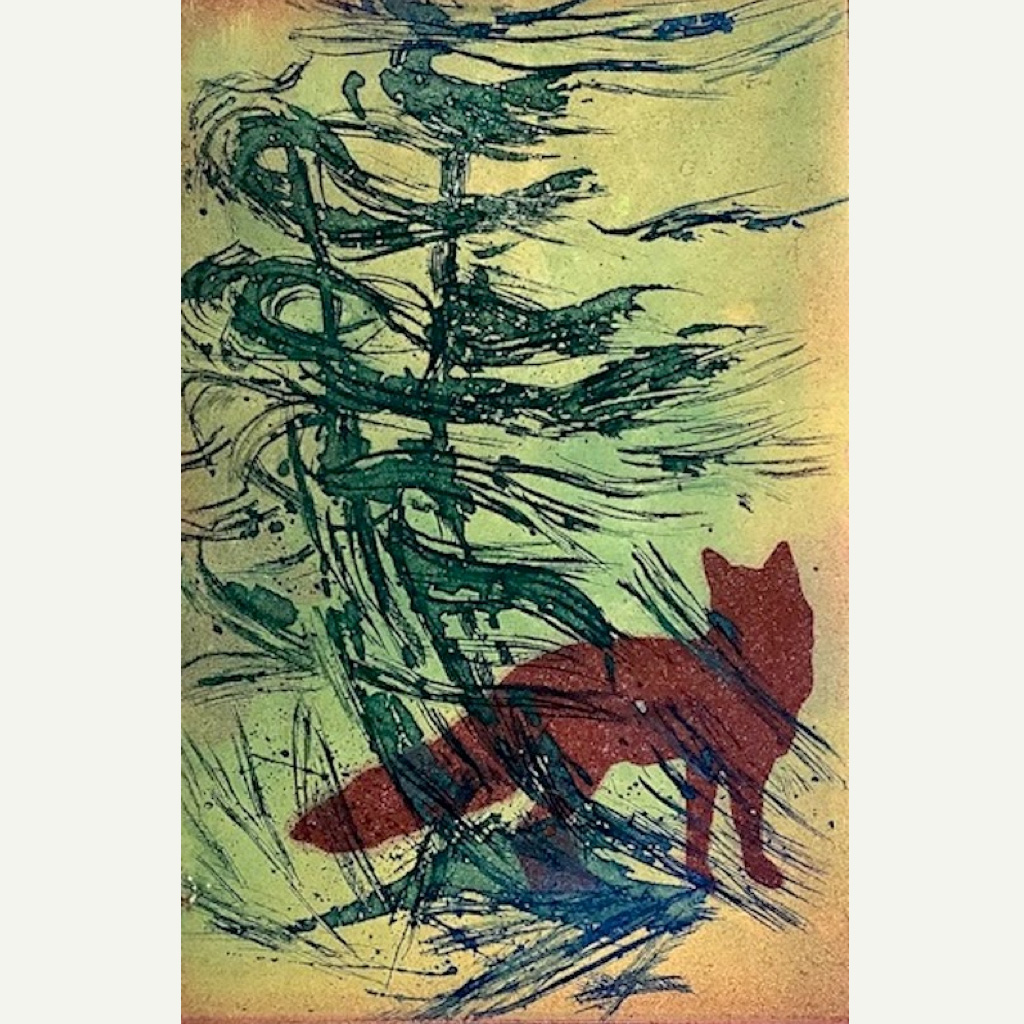

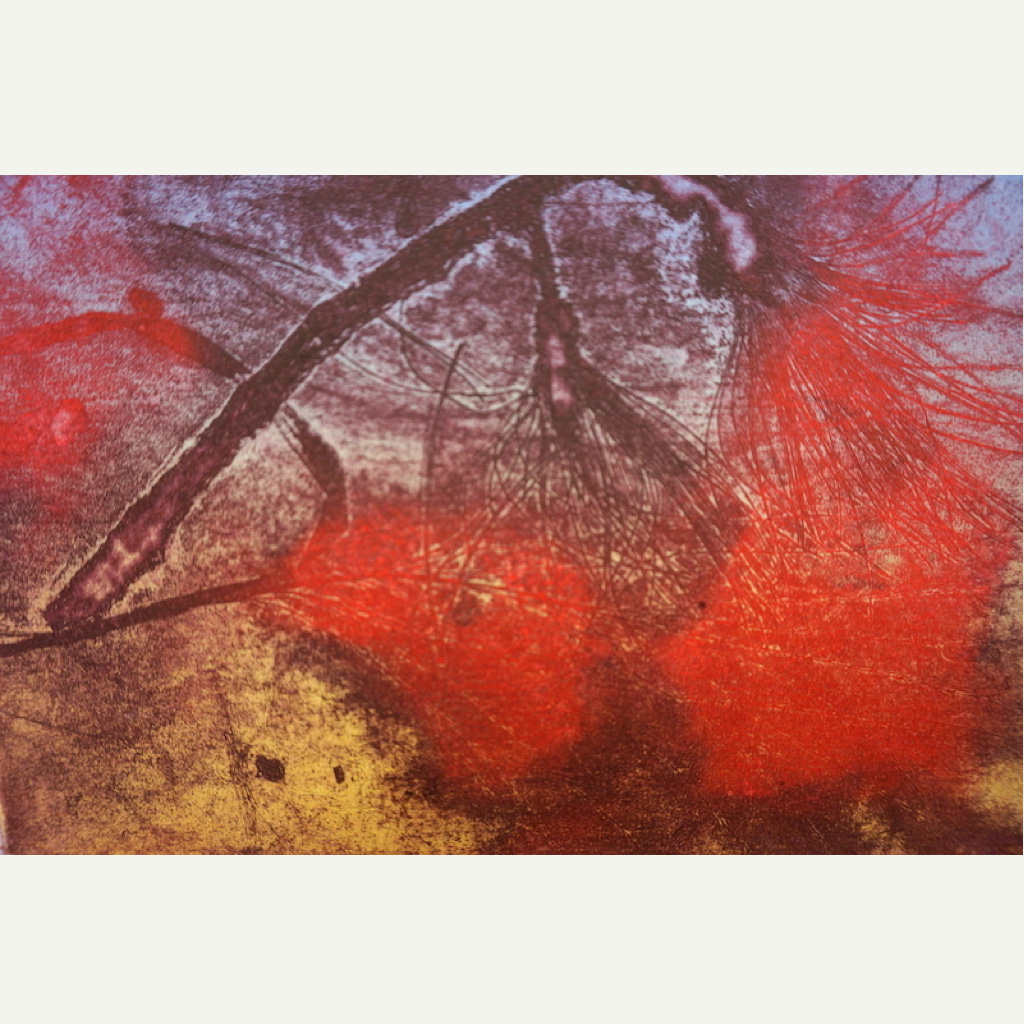

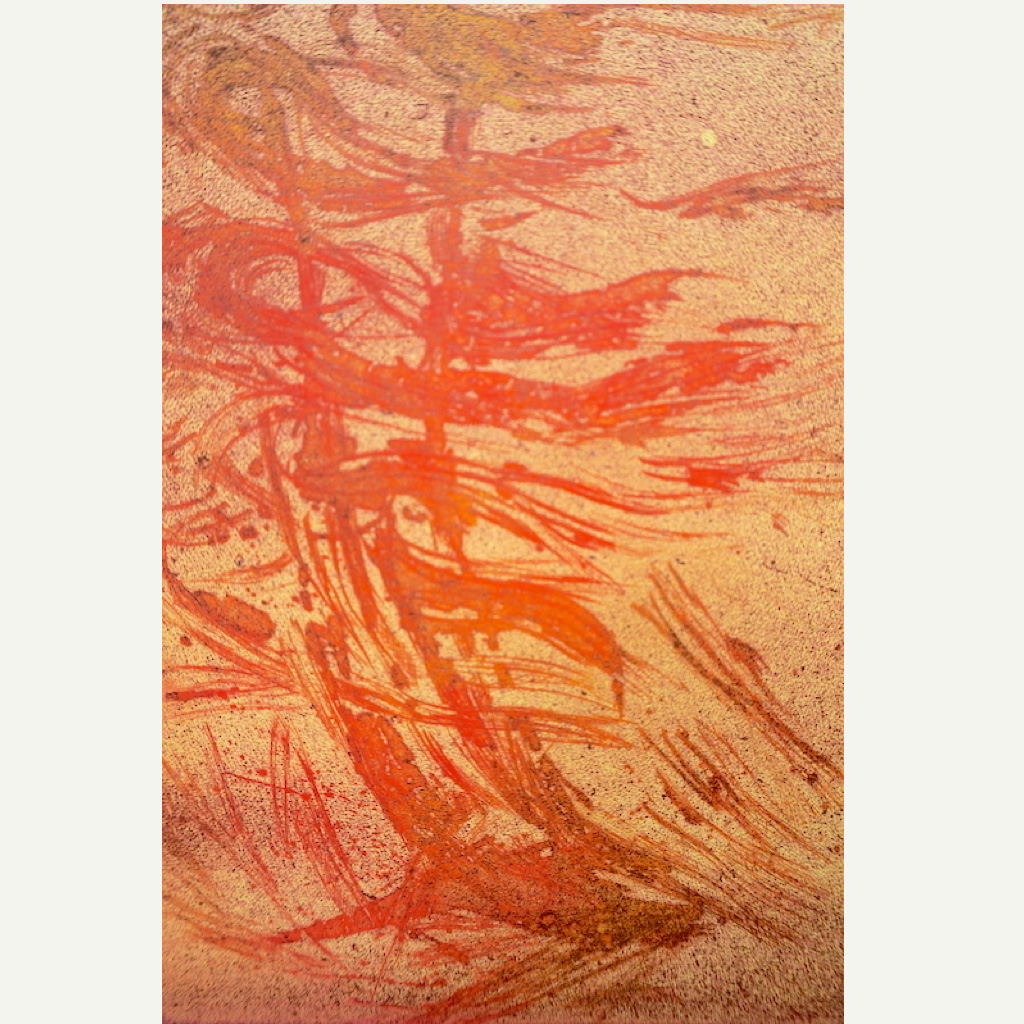

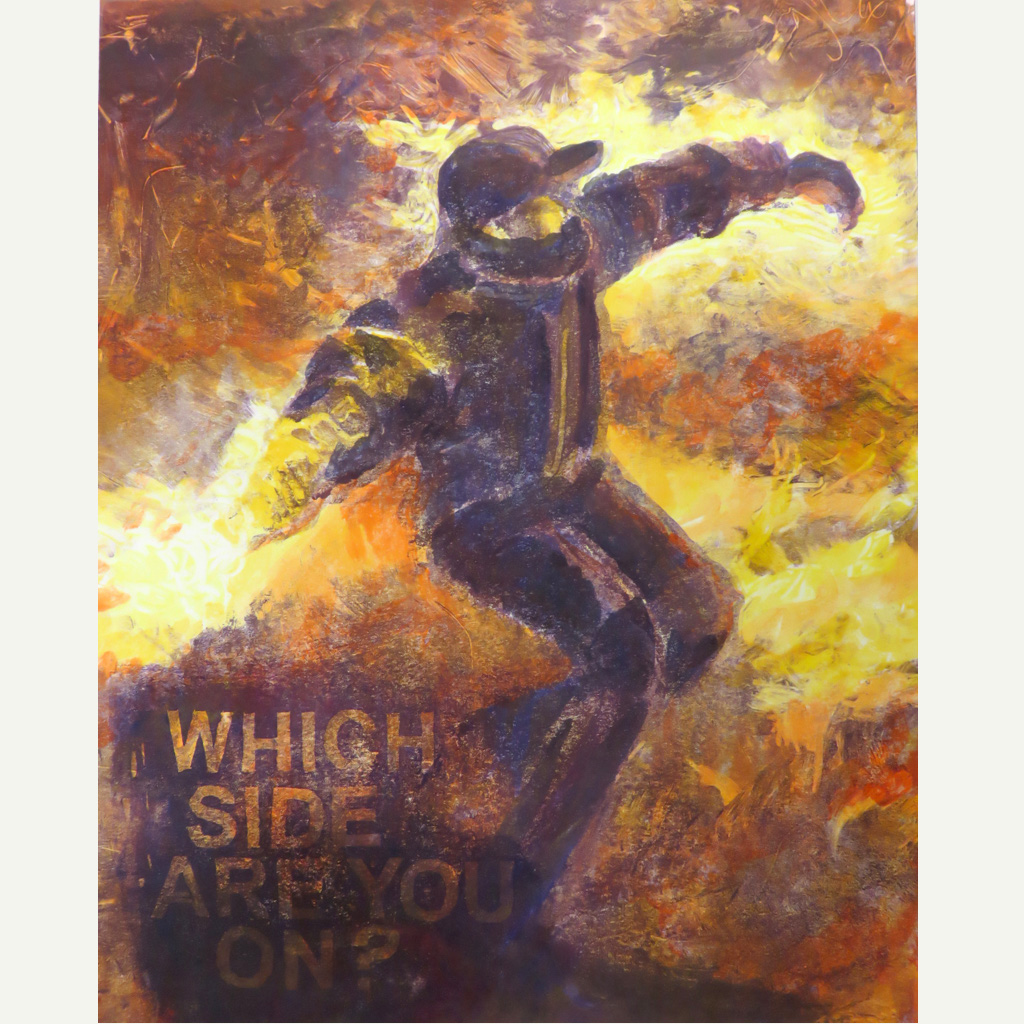

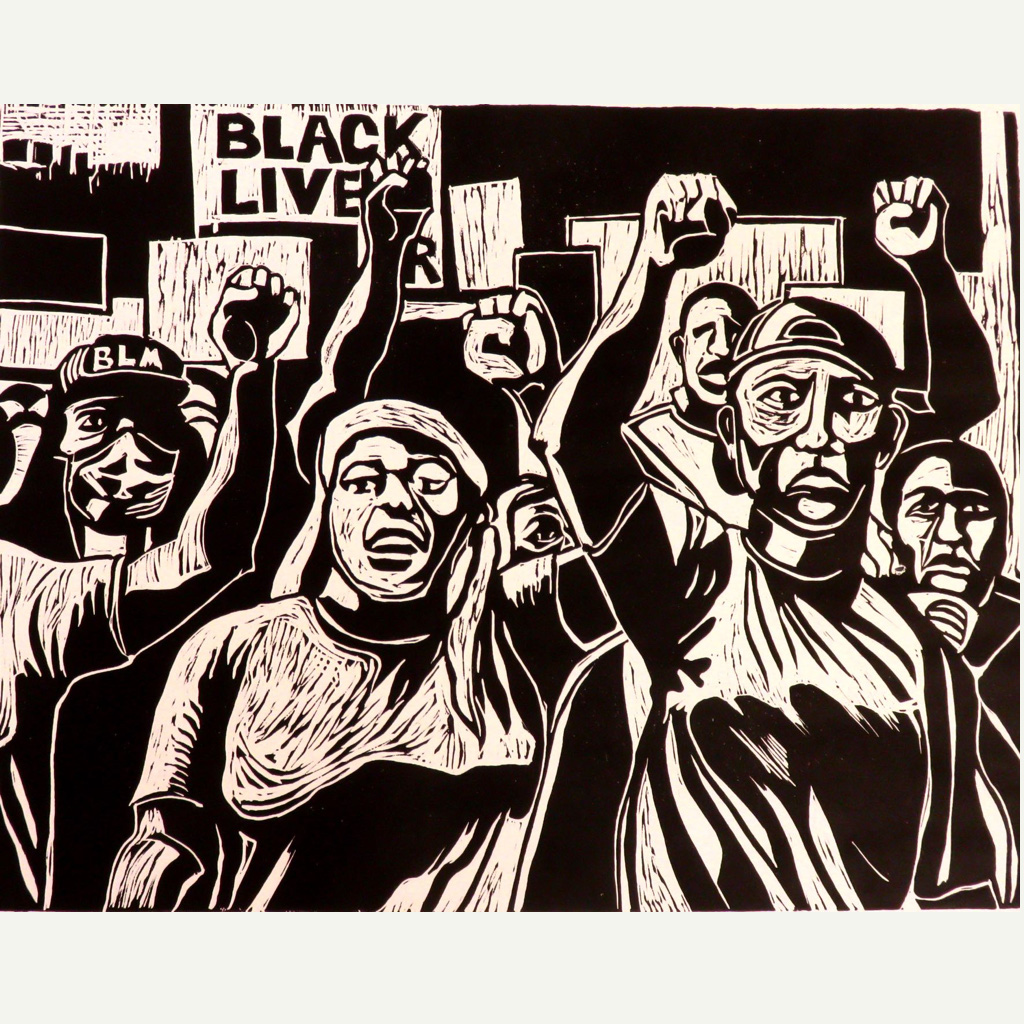

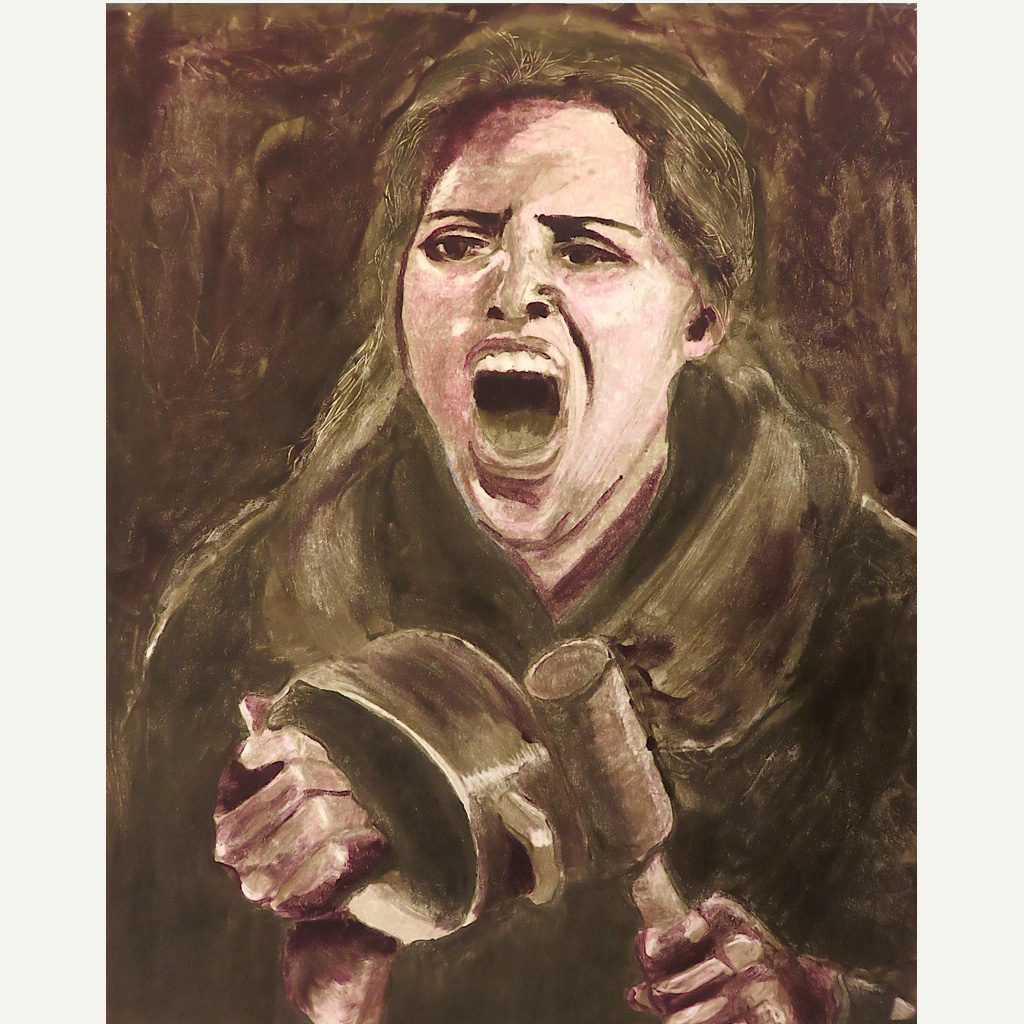

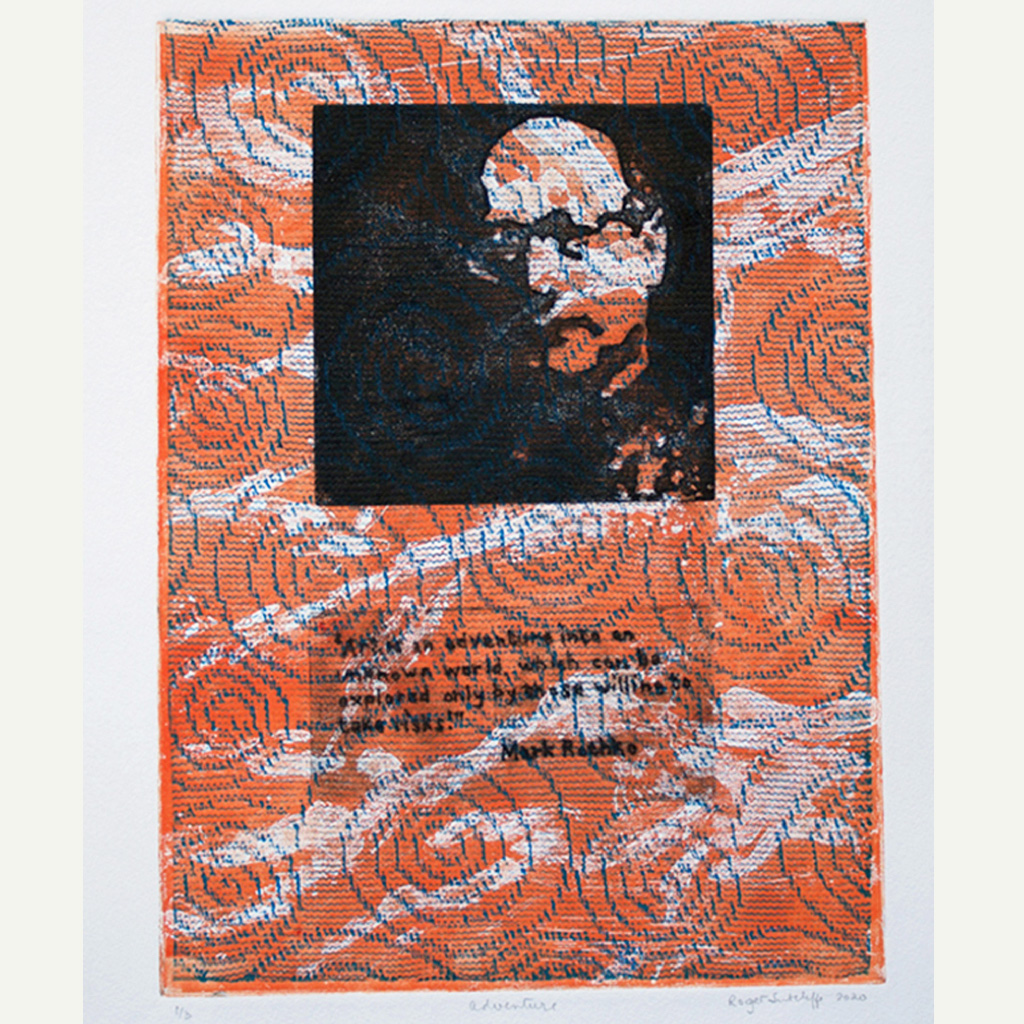

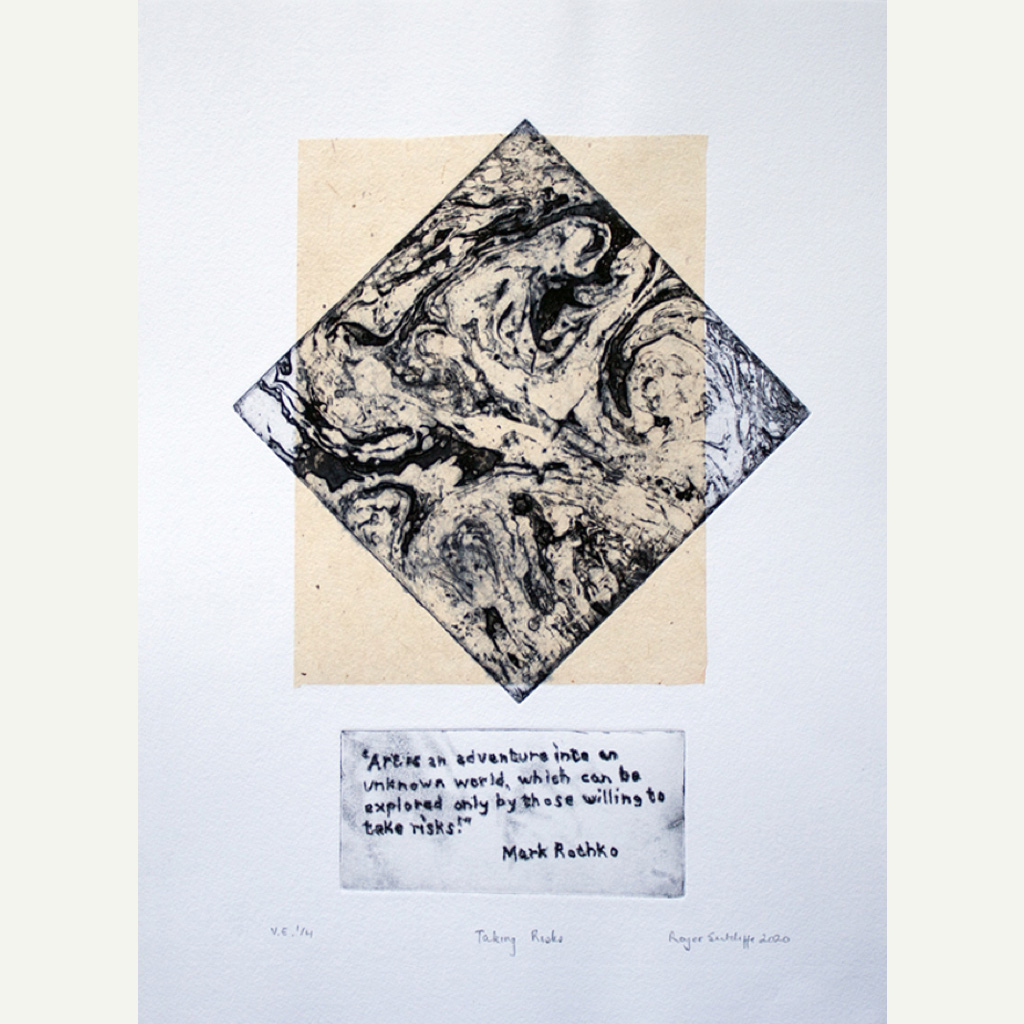

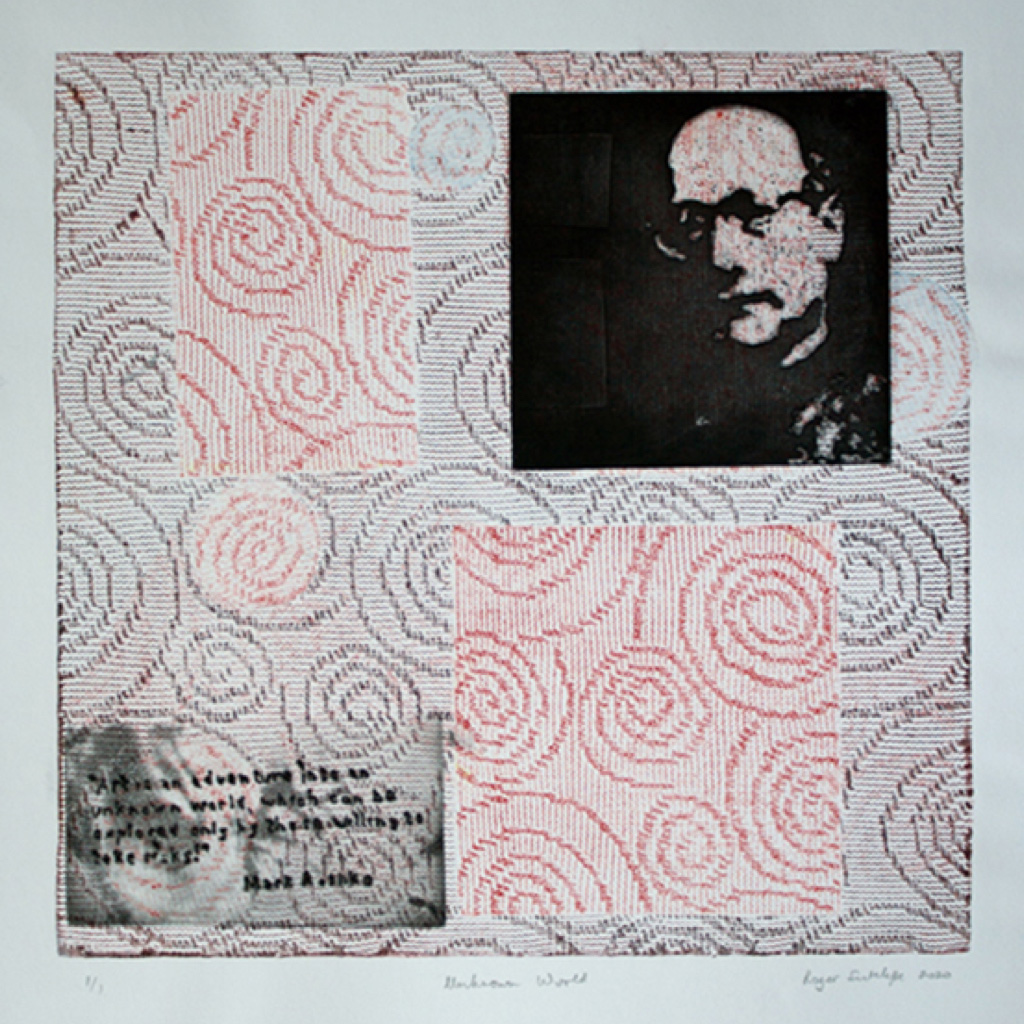

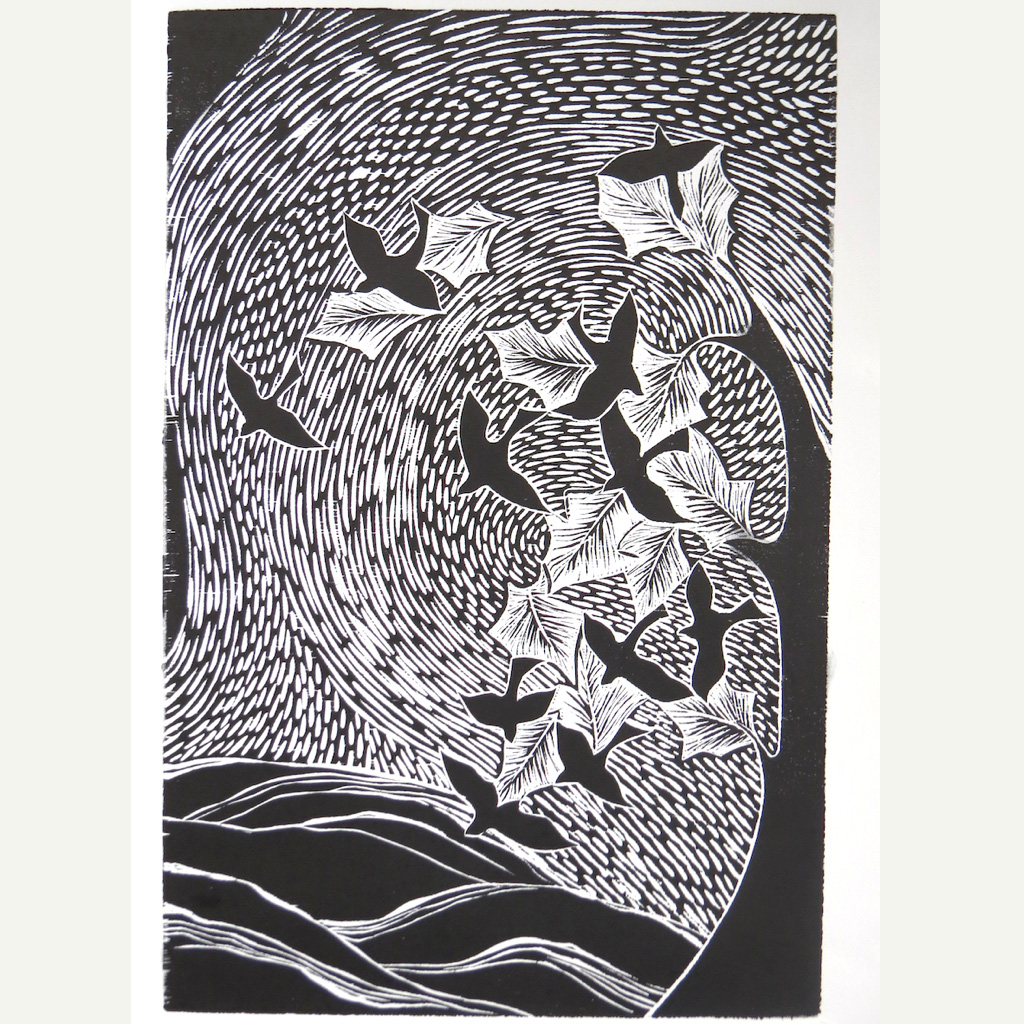

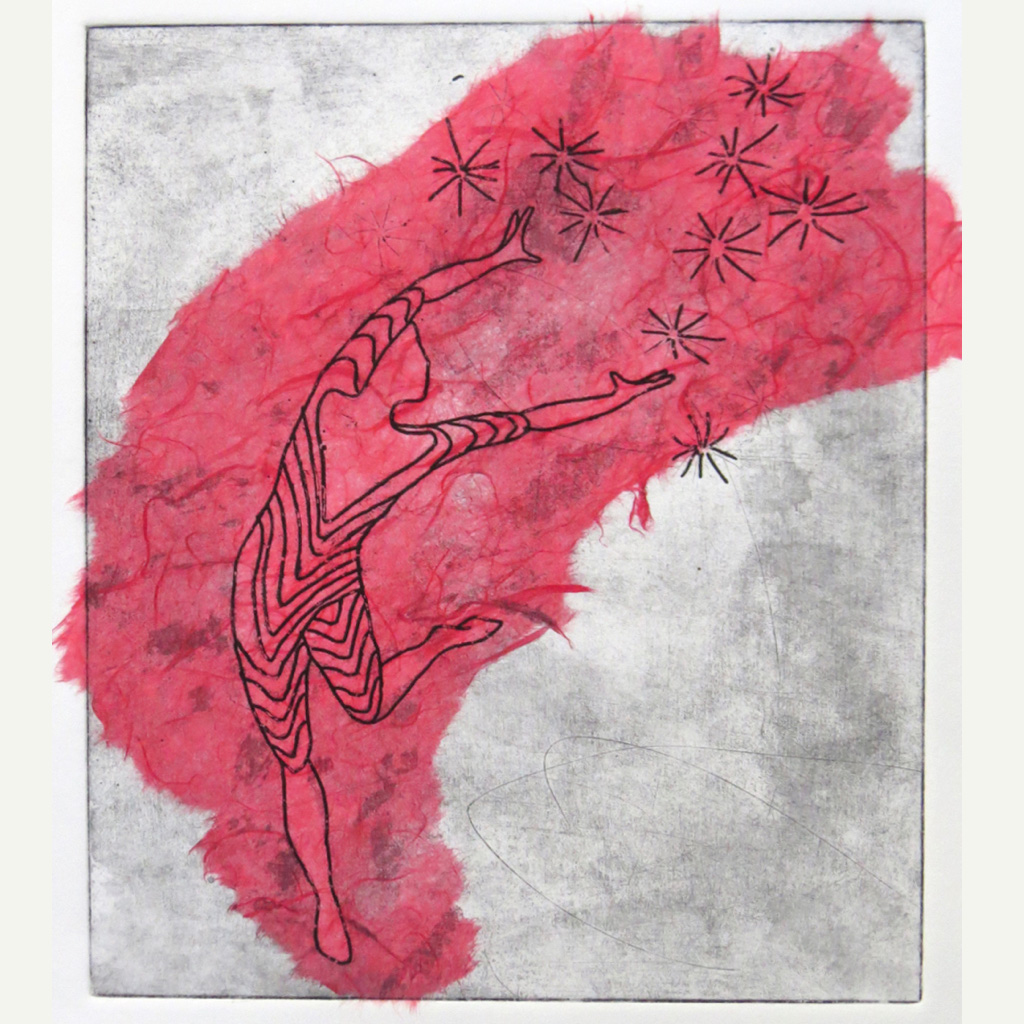

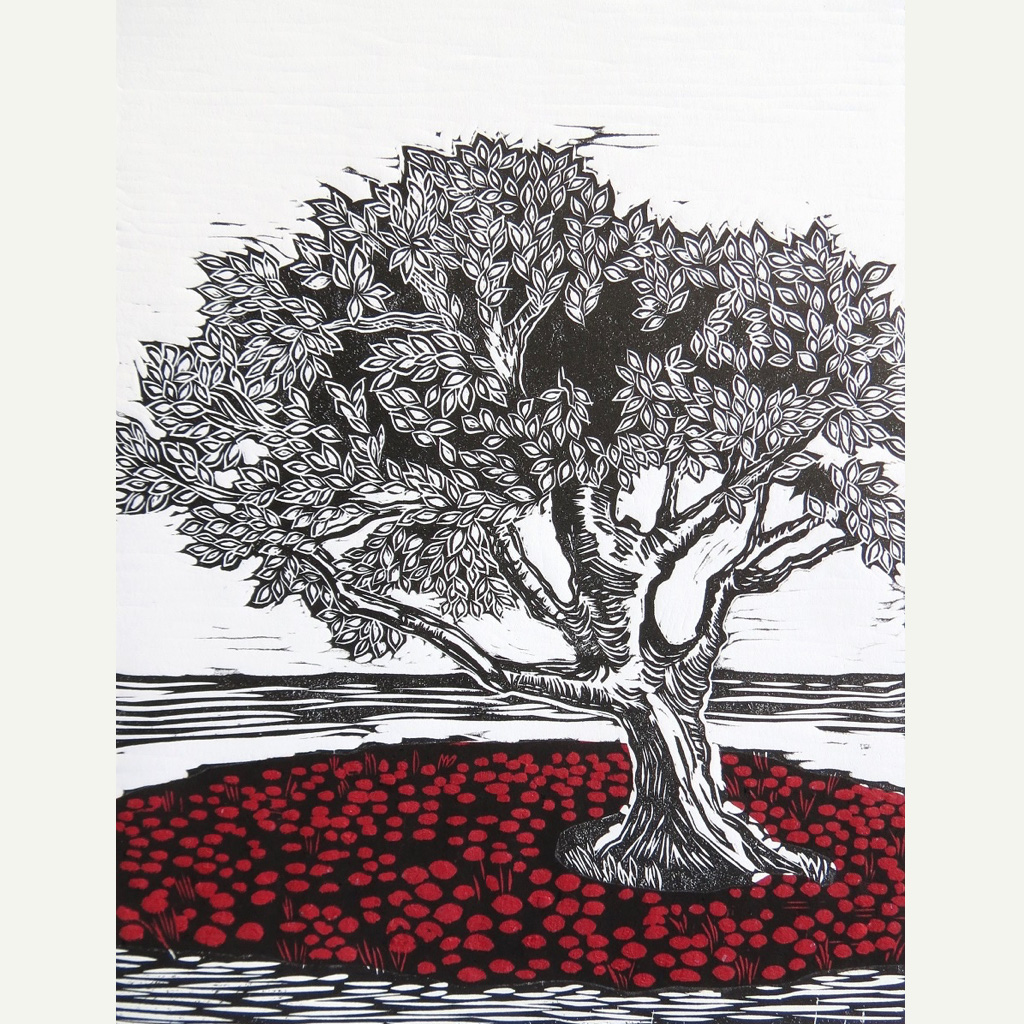

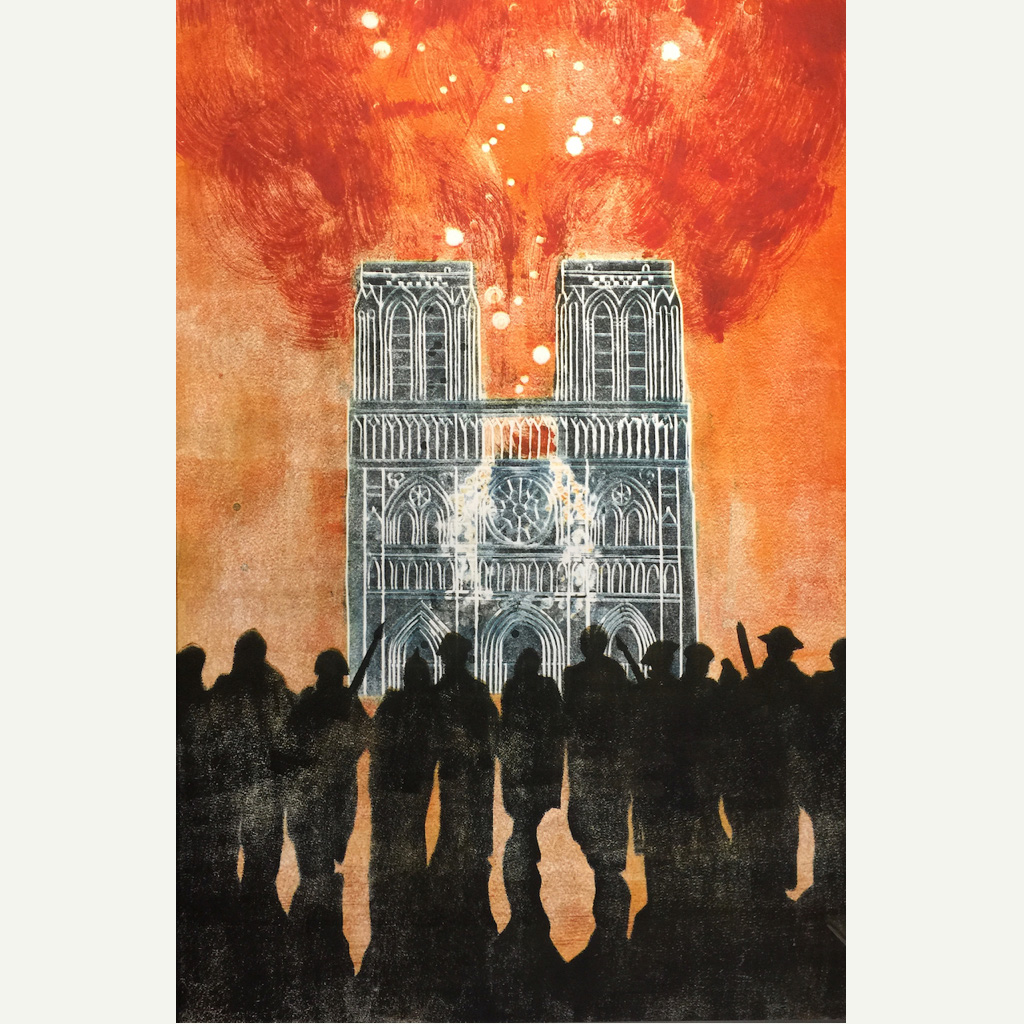

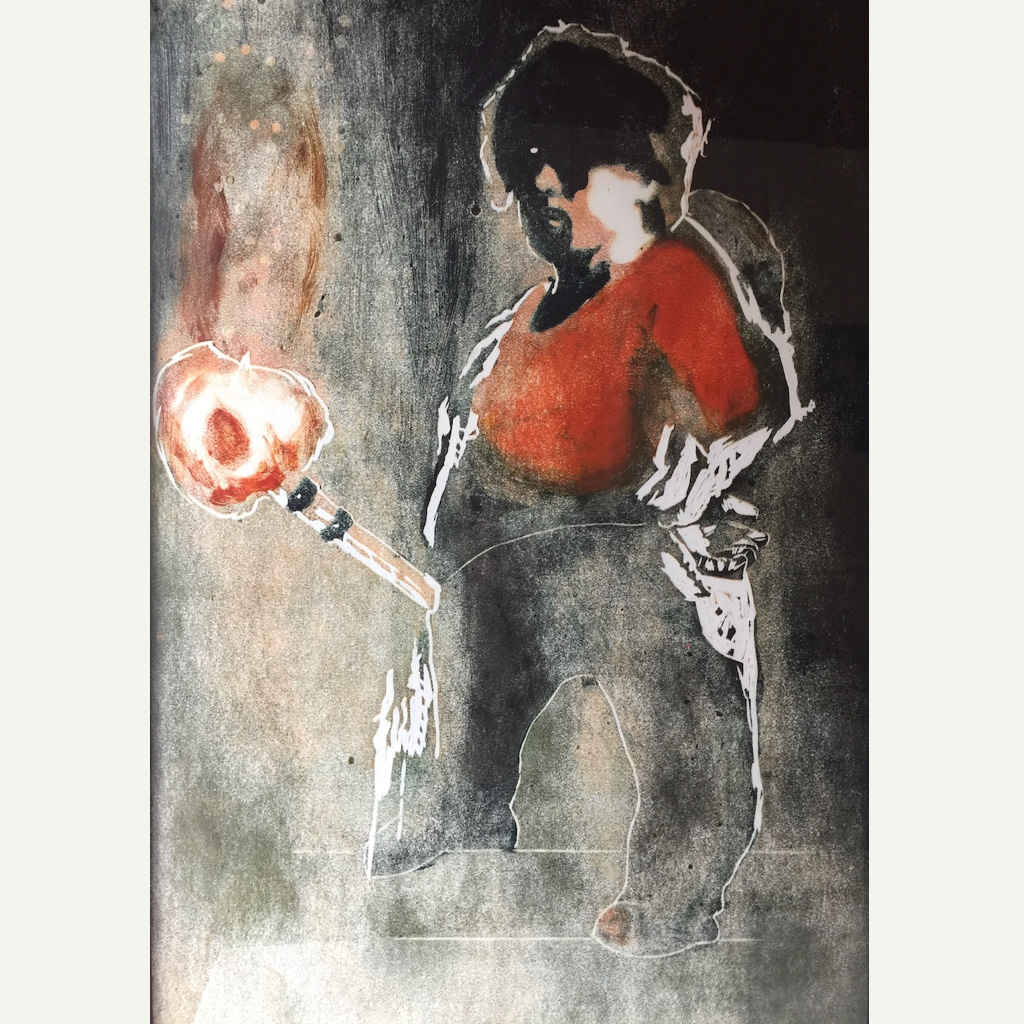

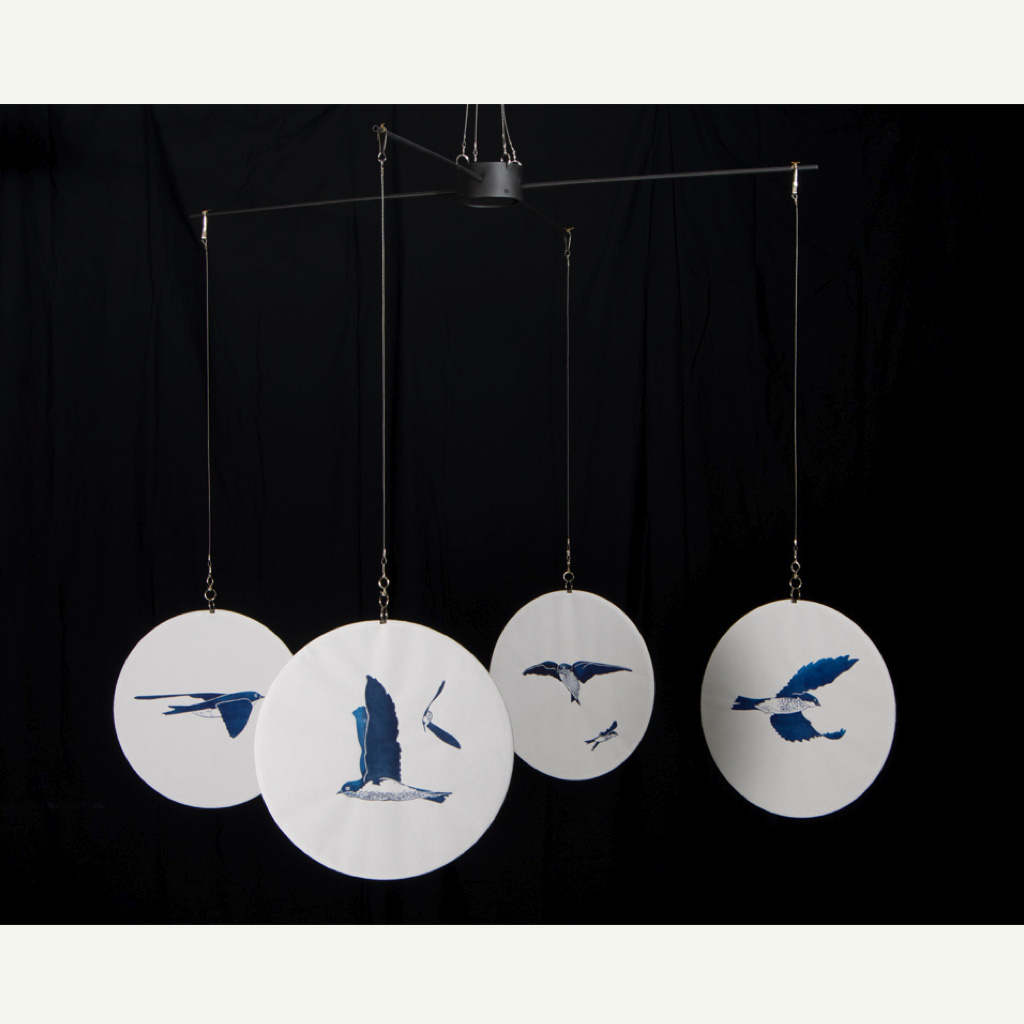

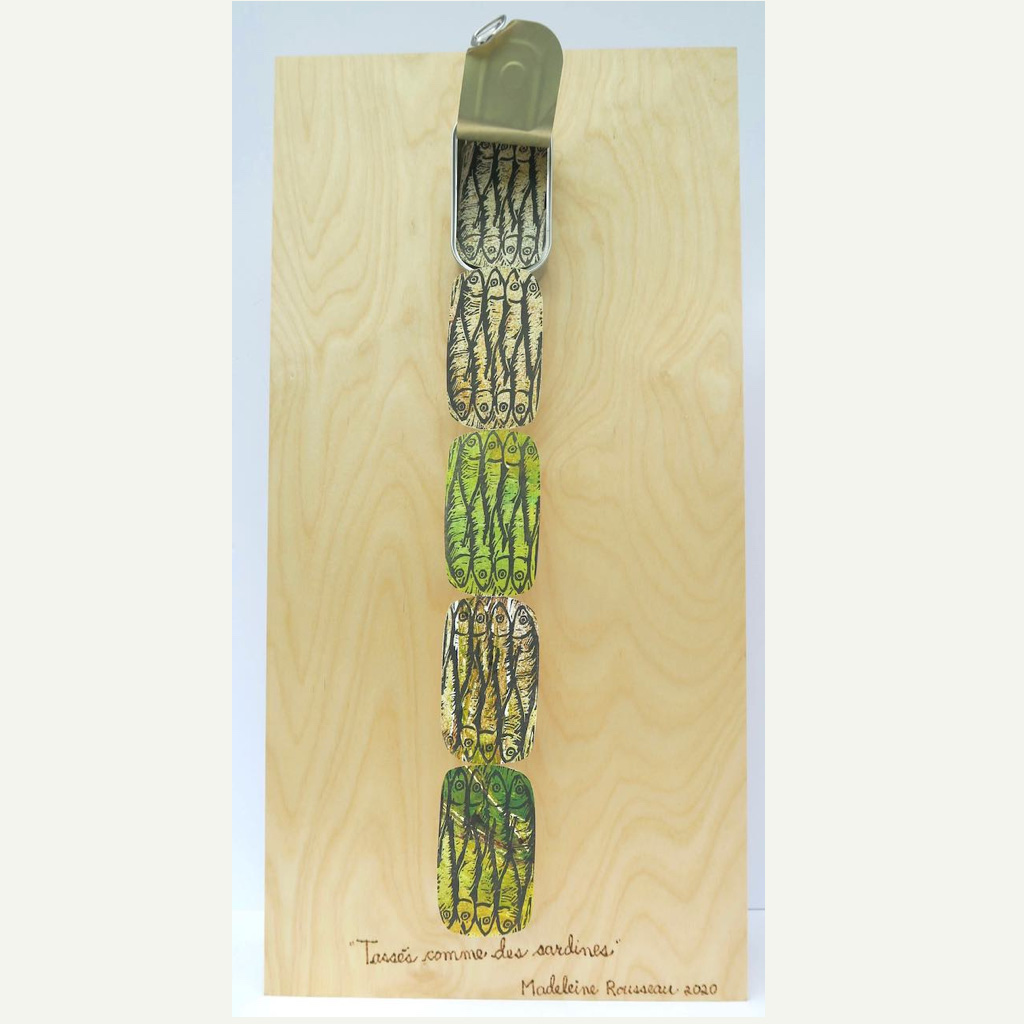

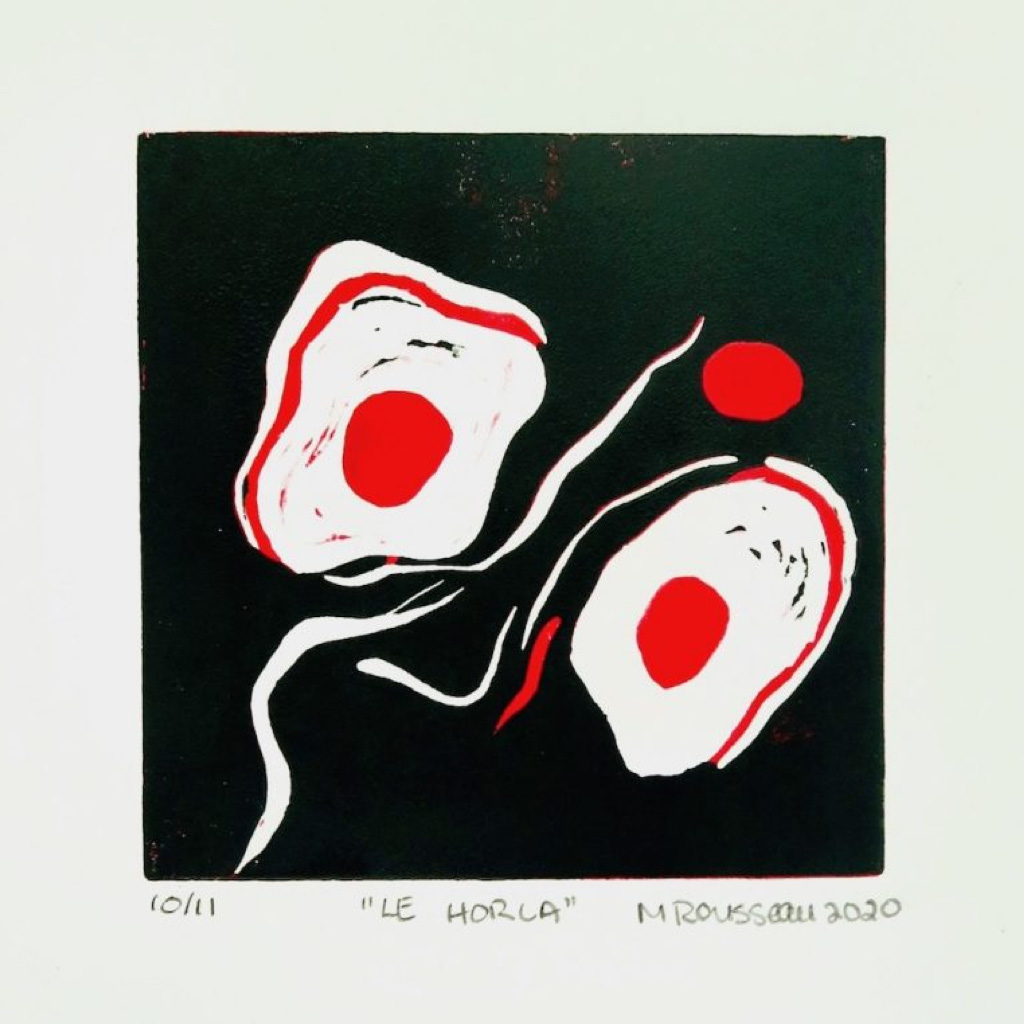

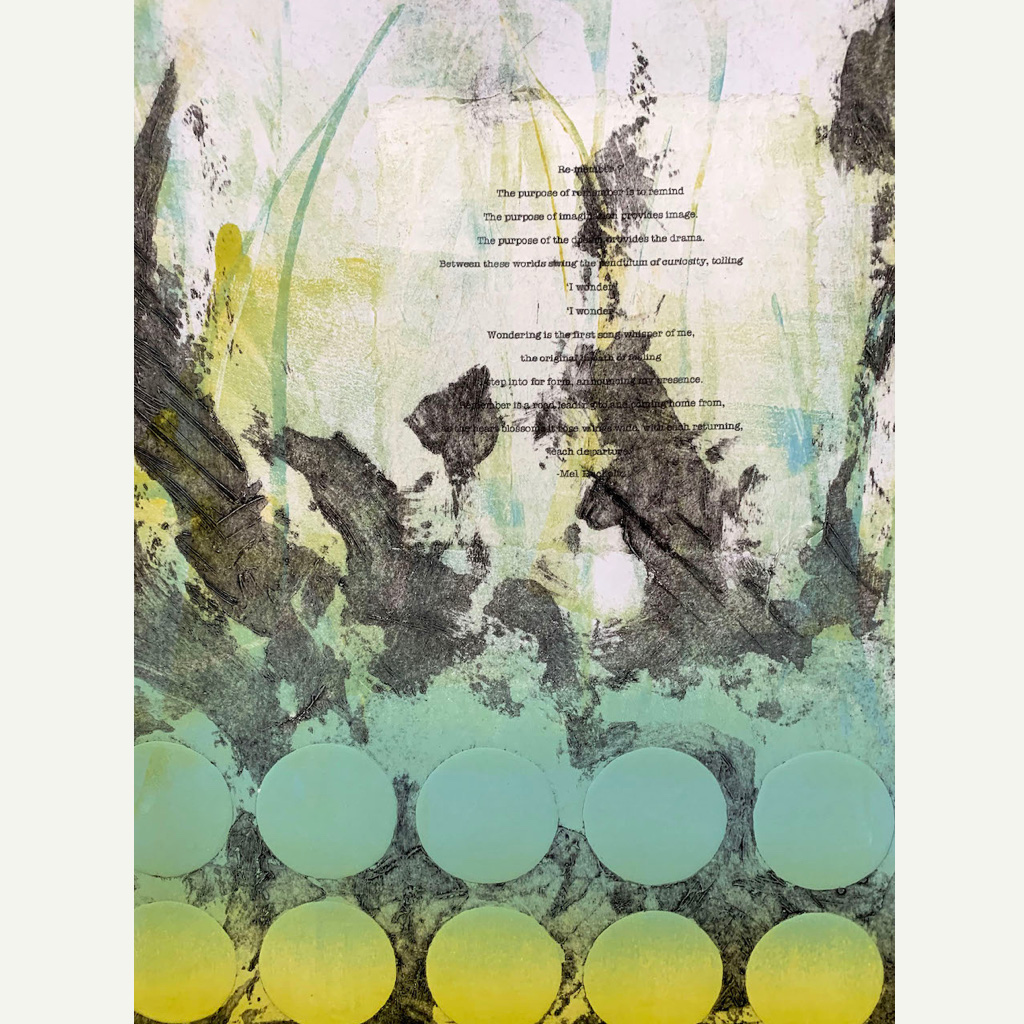

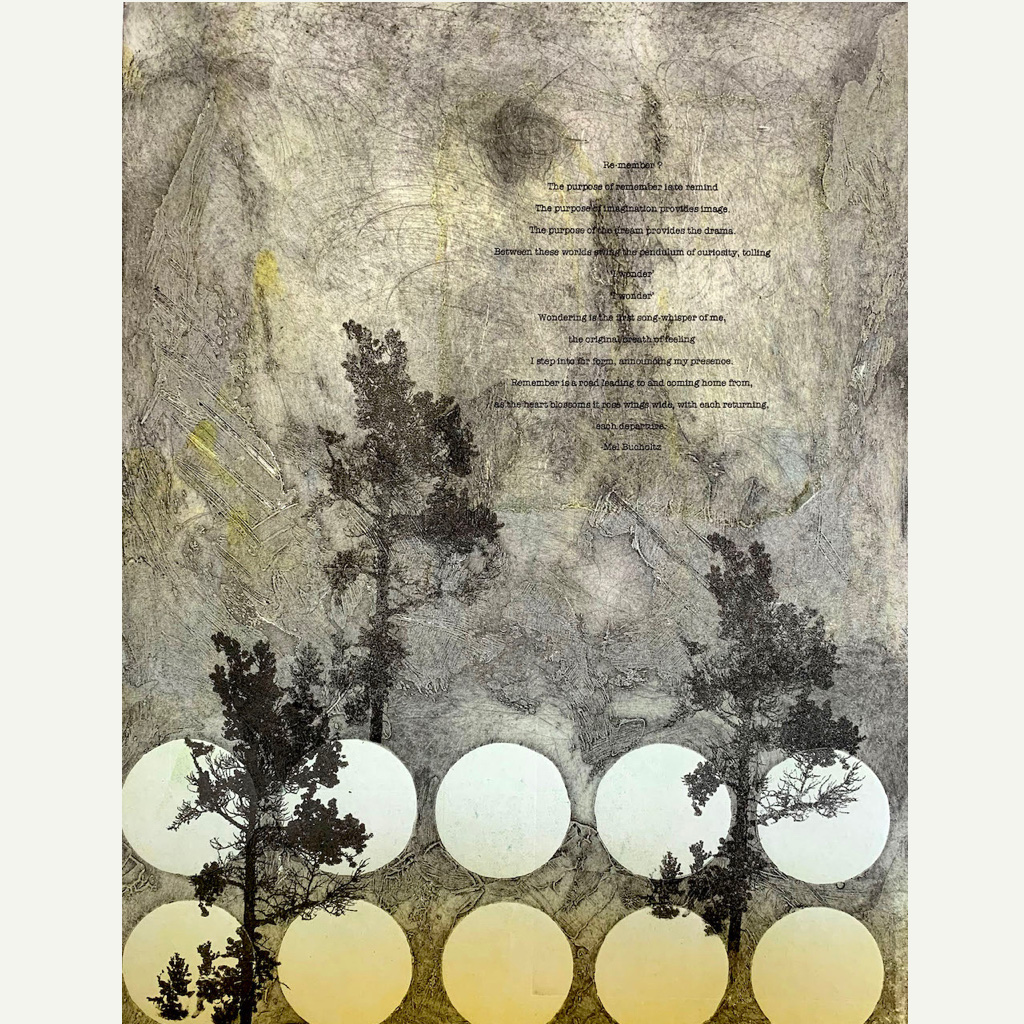

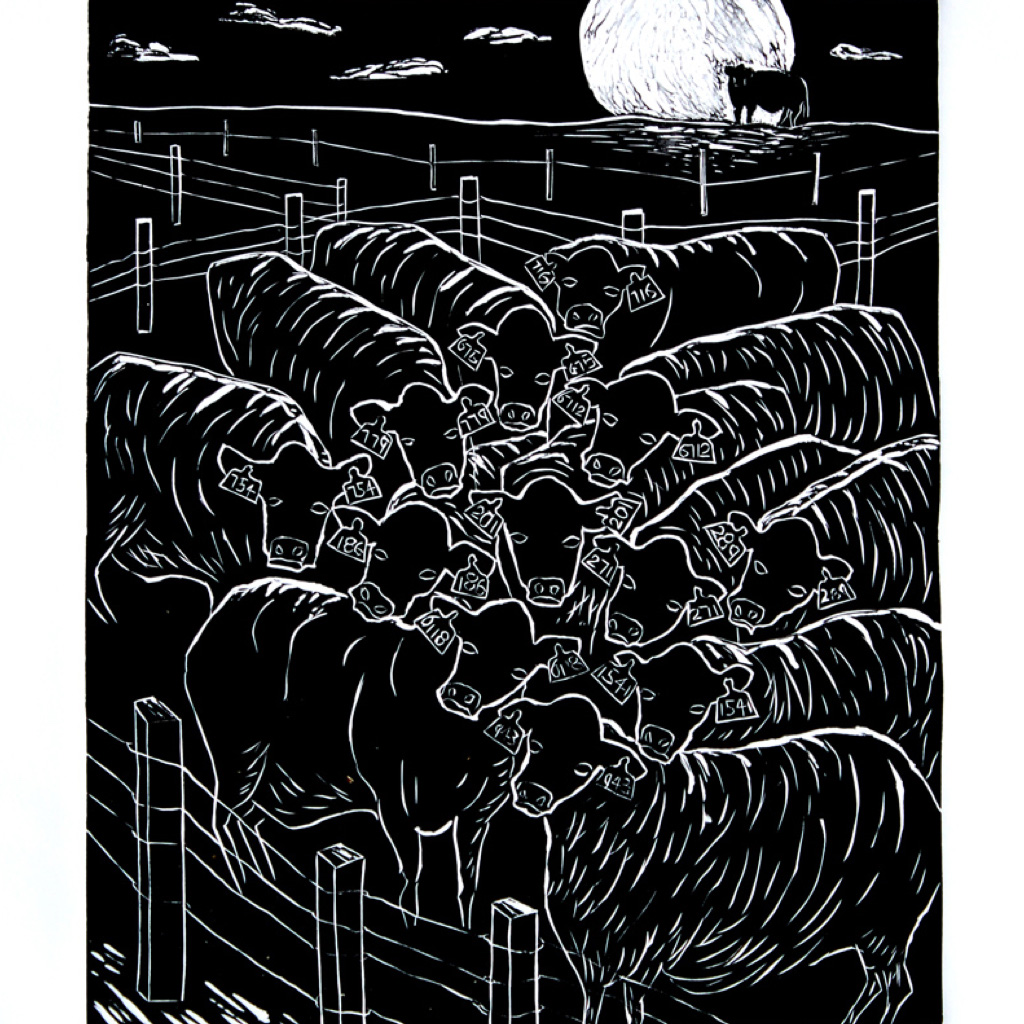

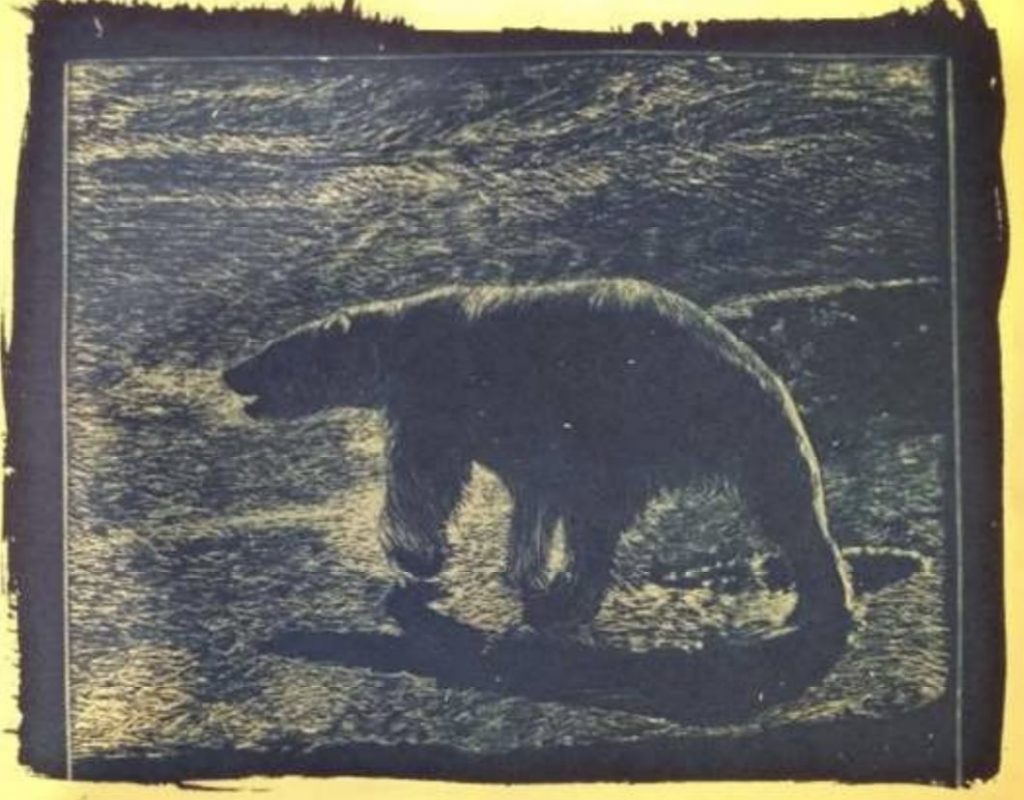

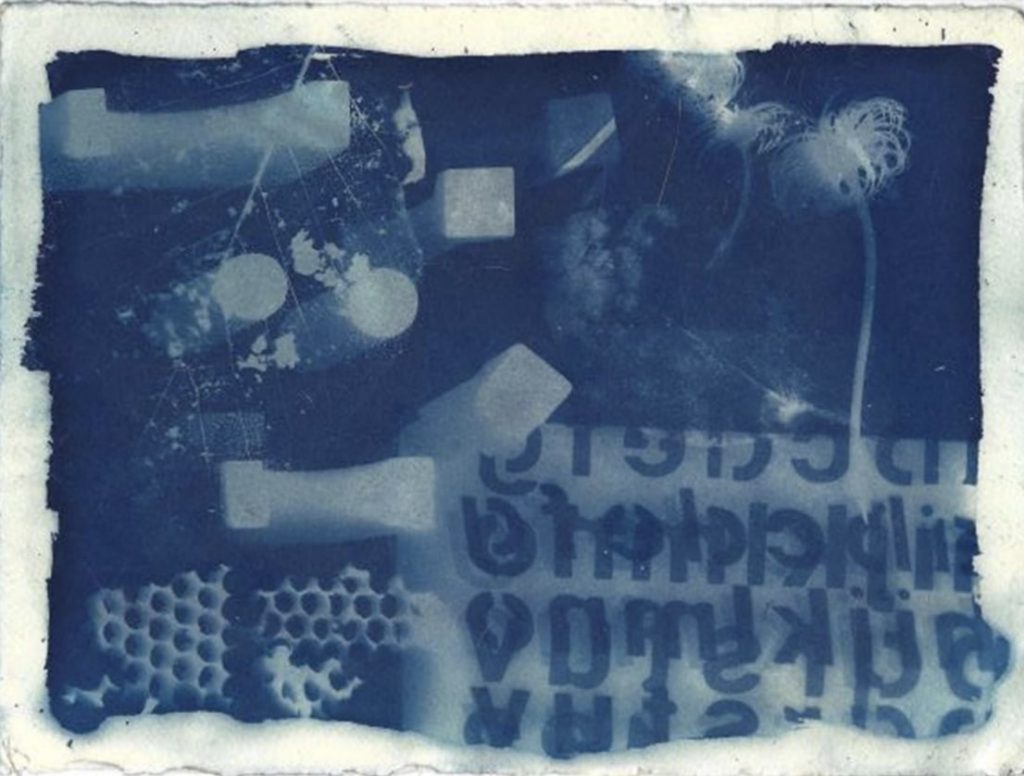

Our current show “Feel the Burr” features a full range of works featuring drypoint, from simple line drawings to works demonstrating a variety of mark making and values shaping the form. While drypoints traditionally are dark ink on white paper, we showcase works that incorporate colour, through the use of coloured inks, multiple plates or the application of coloured paper in a manner know as chine-collé. Because the burr on the plate can quickly break down under the weight of the press, editions are usually very small. Many of the pieces in Feel the Burr are unique prints.

Click here to see virtual exhibition!

La pointe sèche ««Touchez les barbes!»

Nous vivons dans un monde où les images peuvent être reproduites en masse sans fin. Nous pouvons retracer cette histoire à l’invention de l’imprimerie jusqu’à la révolution industrielle. En réponse à la production de masse croissante des images imprimées, les artistes visuels à la fin du 19ème siècle ont relancé la création de la pointe sèche faite à la main.

Les artistes utilisaient un stylet pour rayer les lignes directement dans une matrice de métal tendre, généralement du cuivre. Une fine bavure, ou barbe, serait soulevée de la matrice. La ligne incisée et la barbe retiendront l’encre lorsque la matrice est essuyée. C’est cette barbe très convoitée qui crée les lignes douces et veloutées et la tonalité de la plaque recherchées par les artistes visuels utilisant la pointe sèche.

Aujourd’hui, la technique traditionnelle des pointes sèches est toujours populaire auprès des artistes. Au cours des dernières années, il y a eu une explosion d’expérimentation avec différentes matrices et différents outils. Des outils de dentisterie, des clous et des perceuses électriques peuvent être utilisés pour créer des lignes creux? et des textures sur différents types de matrices plates, comme le PVC, le plexiglas, le plastique d’emballage PETG et même les emballages Tetra aplatis et le contreplaqué. À la suite de ces expériences, la création à la pointe sèche et les arts imprimés en général sont maintenant plus accessibles aux artistes visuels émergents et établis.

Notre exposition actuelle «Touchez les barbes!» présente une gamme complète d’œuvres créées avec la technique de la pointe sèche, allant de simples dessins linéaires à des œuvres déployant une variété de marques et de tonalités? qui façonnent la forme. Alors que les œuvres à la pointe sèche sont traditionnellement réalisées avecde l’encre foncée sur papier blanc, nous présentons des œuvres qui incorporent la couleur, par l’utilisation d’encres colorées, de plaques multiples ou l’application de papier coloré d’une manière appelée chine collé. Parce que la barbe sur la plaque peut rapidement se décomposer sous le poids de la presse, les tirages? sont généralement très petits. Un bon nombre des estampes de «Touchez les barbes!» sont des mono impressions.

Exhibiting Artists (not in order of appearance) / Les artists exposants (pas dans l’ordre d’apparition): Luigina Baratto, Cheryl Beillard, Susan MW Cartwright, Murray Dineen, Carol Howard Donati, Leonard Gerbrandt, Denise Lachance, Aileen Leo, Shealagh Pope, Rod Restivo, Madeleine Rousseau, Beth Shepherd, Patricia Slighte, Dale Shutt, Moira Toomey, and/ et Doug Williams.

Click on the artwork to have more information and see a close-up view./ Cliquez sur l’œuvre d’art pour avoir plus d’informations et voir un gros plan.