by Francine Walker

We were very fortunate and delighted to have Heather McLeod give a presentation on archival matting at our AGM in December. Heather is a professional framer at the National Gallery of Canada; she is also a member of OGPC.

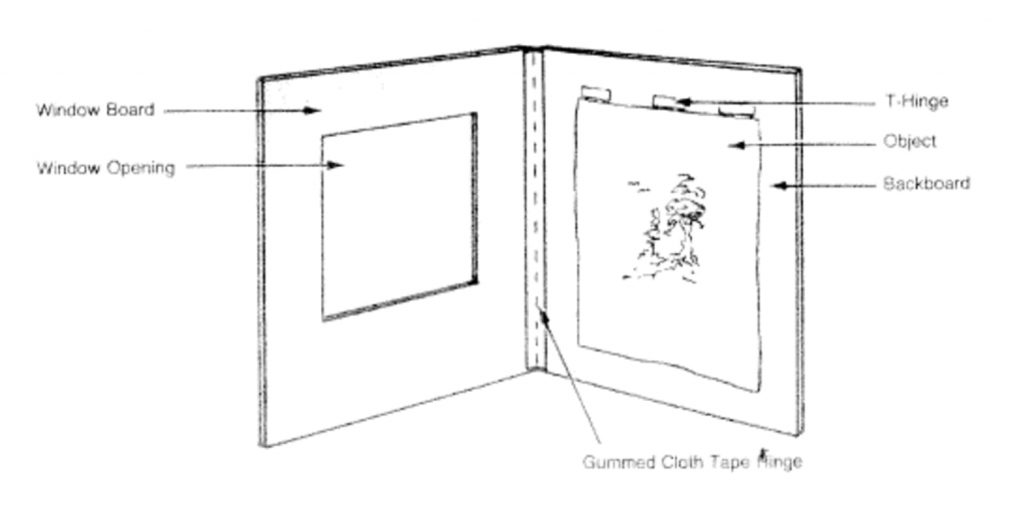

Heather covered a number of aspects on the subject, including a demonstration of how to prepare a mat package with archival products, i.e. how to hinge the mat window to the matboard as well as how to properly secure the artwork to the matboard. She demonstrated the T-hinge, the V-hinge and the pocket method and discussed the importance of using archival quality tape and gummed paper. The products are the following: gummed paper hinging tape and Hayaku or Mulberry hinging paper, both by Lineco as well as Neschen Filmoplast P90.

The hinging tape is thicker and is used to tape the window mat to the backing, usually matboard, in the form of a V. The hinging paper or hinging tissue is thinner and is used to tape the artwork to the matboard. Both are pH neutral and therefore safe for archival and long-term conservation. Another option is to make a pocket or corner piece using archival paper or Japanese paper made from 100% koso fibers and taping it to the matboard. Japanese paper is often used by conservators to make paper hinges. (See articles below for instructions.)

A question was asked on how to prepare a frame when a mat is not required such as for a more contemporary look (also called bleed mounting). Here are 3 possibilities:

- A thin piece of acid-free foam core to fit the rabbet of the frame. This involves cutting and applying glue to either the frame or the foam core, unless the foam core is self-adhesive.

- An acrylic spacer or separator. Spacers are available in black, white or clear. These have the advantage of being inert, therefore archival. They frequently come with an adhesive. The disadvantage is in the cutting. A saw is needed and perhaps a good clamp. However, the look is clean and would not flatten over time. The cost is also a factor. They range from $5-6 at Deserres to $18 at a frame shop. They usually come in 5 ft lengths. Canus Plastics sells a clear spacer in 6 ft lengths for $3.

- Ragboard strips laminated together with archival paste can be attached to the glazing.

To prevent wood lignin and acids from the side of the wood frame migrating to the artwork, it was suggested lining the inside of the frame with metallic tape (the type used to seal a furnace).

This leads us to consider the different types of matboards and the nature of the papers that make up the matboards, i.e. the surface papers, (face and backing) and the core of the matboard.

The following discussion is put together from various online sources and any error of interpretation is entirely mine. However, the URLs referenced below are sourced from recognized expert advice and make for fascinating reading.

What is the difference between Museum, Conservation, White Core and regular mat board?

Essentially, Museum quality matboard has the most exacting standards and would be used for rare and valuable art works. It is made entirely from cotton fibers.

All others, including Conservation, White Core and other regular matboards are made from wood pulp. The wood pulp contains cellulose, lignin & other acids. The lignin and acids would contaminate the paper if they were not removed.

The permanence of the paper/matboard comes from the strength of the fiber and the purity of the cellulose that composes it.

Cotton pulp is mostly cellulose with minute quantities of lignin and is the purest for long-term preservation. For Museum quality, all surfaces of the matboard i.e. the face, back and core papers involved in the lamination process have to be from cotton cellulose.

For matboards made from wood pulp, it is the percentage of cellulosic material present in all surfaces of the lamination that determines whether a matboard can be considered for longer-term conservation. Conservation matboard would have close to 98% cellulose and the lignin content would be no more than 0.65% after processing. This is called “high alpha-cellulose” (some paper makers such as St. Cuthbert’s Mill consider 94% cellulose as conservation quality.) The lignin and other acids such as Sulphur, Iron and Copper present in the wood pulp would have been extracted by mechanical means. The process of de-acidification is done by adding calcium or magnesium bicarbonates to neutralize the acids and bring the pH level of the pulp to 7 or higher. An additional bicarbonate reserve is added to act as a buffer on the paper so that acids which could migrate over the years would be neutralized by the bicarbonates. Over time, (a few decades and up to 100 years) it is possible that the reserve of carbonates would no longer be able to neutralize the acids, and the paper could suffer yellowing and possibly some deterioration. These are considered archival.

pH neutrality is truly applicable to aqueous solutions where it is possible to control the balance between hydrogen ions. In other mediums such as paper, especially wood-pulp based paper, other ions are present such that adjusting the pH level is a matter of introducing counterbalancing agents such as bicarbonates to make the solution more alkaline. The term acid free is often used incorrectly as a synonym for lignin-free.

All Museum quality is archival but not all archival is museum quality. For example, Conservation matboard is considered archival because of its high alpha-cellulose content. But it would not be Museum quality.

The term “archival” is nontechnical and can be misleading, broadly suggesting that a material is permanent or chemically stable. The term is not quantifiable as no standards exist that describe the exact qualities of an “archival” material. This definition is from the PPFA, the Professional Picture Framers Association.

Today, most regular matboards have some basic treatment to neutralize against the excessive acidity that is released when lignin, the binding polymer in wood, breaks down. But regular matboards should not be used to frame serious artworks.

Environmental conditions, such as humidity, light exposure, lightfastness of colored matboard, sizing, pollutants, as well as inappropriate framing techniques could cause deterioration of the artwork over time. Of course, the chemicals present in the ink as well as poor quality printing paper could also affect the artwork.

The major matboard company in Canada is Peterboro Matboards. They have 3 classifications for their matboards.

- Museum grade: 100% cotton fibers.

- Conservation quality: high alpha-cellulose (98%); made from wood pulp.

- White Core quality: slightly lower alpha-cellulose, made from wood pulp. The surface and backing are acid free, while the core would not be acid-free and would contain optical brighteners to prevent discoloration. White Core grade matboard is not suitable for preservation matting.

Peterboro also makes a 2-ply 100% cotton board, which can be used for various mounting purposes such as an interleaf. It is available at DeSerres in a 16”X20” sheet.

As a complement to Heather McLeod’s presentation at the AGM, here are 5 references for those who were unable to attend the AGM. You will find demonstrations of the various methods of hinging as well as technical information on paper classification. The articles by Hugh Phibbs are particularly interesting. Mr. Phibbs was Coordinator of the Preservation Services, Conservation Division of the National Gallery of Art, Washington, DC.

- Library of Congress, Matting and Hinging of Works of Art on Paper [PDF: 2 MB / 32 pp.]. Compiled and illustrated by the Library of Congress Conservation Division.

- Northeast Document Conservation Center, Matting and Framing for Art and Artifacts on Paper

- Hugh Phibbs, “Preservation Matting for Works of Art on Paper” [PDF: 307 KB / 24 pp.]

- Recent Developments in Preservation of Works on Paper by Hugh Phibbs, https://cool.conservation-us.org/coolaic/sg/bpg/annual/v24/bp24-10.pdf

- The determination of the alpha-cellulose content and copper number of paper. https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/jres/6/jresv6n4p603_A2b.pdf